Planet Python

Last update: February 27, 2026 07:44 PM UTC

February 27, 2026

Real Python

The Real Python Podcast – Episode #286: Overcoming Testing Obstacles With Python's Mock Object Library

Do you have complex logic and unpredictable dependencies that make it hard to write reliable tests? How can you use Python's mock object library to improve your tests? Christopher Trudeau is back on the show this week with another batch of PyCoder's Weekly articles and projects.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

February 27, 2026 12:00 PM UTC

Quiz: Dependency Management With Python Poetry

Test your understanding of Dependency Management With Python Poetry.

You’ll revisit how to install Poetry the right way, create new projects, manage virtual environments, declare and group dependencies, work with lock files, and keep your dependencies up to date.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

February 27, 2026 12:00 PM UTC

Ned Batchelder

Pytest parameter functions

Pytest’s parametrize is a great feature for writing tests without repeating yourself needlessly. (If you haven’t seen it before, read Starting with pytest’s parametrize first). When the data gets complex, it can help to use functions to build the data parameters.

I’ve been working on a project involving multi-line data, and the parameterized test data was getting awkward to create and maintain. I created helper functions to make it nicer. The actual project is a bit gnarly, so I’ll use a simpler example to demonstrate.

Here’s a function that takes a multi-line string and returns two numbers, the lengths of the shortest and longest non-blank lines:

def non_blanks(text: str) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""Stats of non-blank lines: shortest and longest lengths."""

lengths = [len(ln) for ln in text.splitlines() if ln]

return min(lengths), max(lengths)

We can test it with a simple parameterized test with two test cases:

import pytest

from non_blanks import non_blanks

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"text, short, long",

[

("abcde\na\nabc\n", 1, 5),

("""\

A long line

The next line is blank:

Short.

Much much longer line, more than anyone thought.

""", 6, 48),

]

)

def test_non_blanks(text, short, long):

assert non_blanks(text) == (short, long)

I really dislike how the multi-line string breaks the indentation flow, so I wrap strings like that in textwrap.dedent:

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"text, short, long",

[

("abcde\na\nabc\n", 1, 5),

(textwrap.dedent("""\

A long line

The next line is blank:

Short.

Much much longer line, more than anyone thought.

"""),

6, 48),

]

)

(For brevity, this and following examples only show the parametrize decorator, the test function itself stays the same.)

This looks nicer, but I have to remember to use dedent, which adds a little bit of visual clutter. I also need to remember that first backslash so that the string won’t start with a newline.

As the test data gets more elaborate, I might not want to have it all inline in the decorator. I’d like to have some of the large data in its own file:

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"text, short, long",

[

("abcde\na\nabc\n", 1, 5),

(textwrap.dedent("""\

A long line

The next line is blank:

Short.

Much much longer line, more than anyone thought.

"""),

6, 48),

(Path("gettysburg.txt").read_text(), 18, 80),

]

)

Now things are getting complicated. Here’s where a function can help us. Each test case needs a string and three numbers. The string is sometimes provided explicitly, sometimes read from a file.

We can use a function to create the correct data for each case from its most convenient form. We’ll take a string and use it as either a file name or literal data. We’ll deal with the initial newline, and dedent the multi-line strings:

def nb_case(text, short, long):

"""Create data for test_non_blanks."""

if "\n" in text:

# Multi-line string: it's actual data.

if text[0] == "\n": # Remove a first newline

text = text[1:]

text = textwrap.dedent(text)

else:

# One-line string: it's a file name.

text = Path(text).read_text()

return (text, short, long)

Now the test data is more direct:

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"text, short, long",

[

nb_case("abcde\na\nabc\n", 1, 5),

nb_case("""

A long line

The next line is blank:

Short.

Much much longer line, more than anyone thought.

""",

6, 48),

nb_case("gettysburg.txt", 18, 80),

]

)

One nice thing about parameterized tests is that pytest creates a distinct id for each one. The helps with reporting failures and with selecting tests to run. But the id is made from the test data. Here, our last test case has an id using the entire Gettysburg Address, over 1500 characters. It was very short for a speech, but it’s very long for an id!

This is what the pytest output looks like with our current ids:

test_non_blank.py::test_non_blanks[abcde\na\nabc\n-1-5] PASSED

test_non_blank.py::test_non_blanks[A long line\nThe next line is blank:\n\nShort.\nMuch much longer line, more than anyone thought.\n-6-48] PASSED

test_non_blank.py::test_non_blanks[Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a\nnew nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men\nare created equal.\n\nNow we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any\nnation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great\nbattle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a\nfinal resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might\nlive. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.\n\nBut, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate \u2013 we can not consecrate we can not\nhallow \u2013 this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have\nconsecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little\nnote, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did\nhere. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished\nwork which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather\nfor us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from\nthese honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave\nthe last full measure of devotion \u2013 that we here highly resolve that these dead\nshall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth\nof freedom \u2013 and that government of the people, by the people, for the people,\nshall not perish from the earth.\n-18-80] PASSED

Even that first shortest test has an awkward and hard to use test name.

For more control over the test data, instead of creating tuples to use as test cases, you can use pytest.param to create the internal parameters object that pytest needs. Each of these can have an explicit id assigned. Pytest will still assign an id if you don’t provide one.

Here’s an updated nb_case() function using pytest.param:

def nb_case(text, short, long, id=None):

if "\n" in text:

# Multi-line string: it's actual data.

if text[0] == "\n": # Remove a first newline

text = text[1:]

text = textwrap.dedent(text)

else:

# One-line string: it's a file name.

id = id or text

text = Path(text).read_text()

return pytest.param(text, short, long, id=id)

Now we can provide ids for test cases. The ones reading from a file will use the file name as the id:

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"text, short, long",

[

nb_case("abcde\na\nabc\n", 1, 5, id="little"),

nb_case("""

A long line

The next line is blank:

Short.

Much much longer line, more than anyone thought.

""",

6, 48, id="four"),

nb_case("gettysburg.txt", 18, 80),

]

)

Now our tests have useful ids:

test_non_blank.py::test_non_blanks[little] PASSED

test_non_blank.py::test_non_blanks[four] PASSED

test_non_blank.py::test_non_blanks[gettysburg.txt] PASSED

The exact details of my case() function aren’t important here. Your

tests will need different helpers, and you might make different decisions about

what to do for these tests. But a function like this lets you write your complex

test cases in the way you like best to make your tests as concise, expressive

and readable as you want.

February 27, 2026 11:53 AM UTC

Seth Michael Larson

Deprecate confusing APIs like “os.path.commonprefix()”

The os.path.commonprefix() function has been an API in the Python

standard library for at least 35 years (since February 1991)

and in that time has been confusing users and creating security

issues, even in programs explicitly trying to mitigate vulnerabilities.

This was caused directly by the API's placement in the os.path module

and further perpetuated by backwards compatibility.

Here are my top-level takeaways from investigating this issue:

- Weigh surprise and potential for misuse higher than backwards compatibility. Deprecate, rename, and remove security-relevant functions that aren't designed to prevent accidental misuse.

- An API's “fitness for purpose” is implied to users through an API's “labeling” (such as: module, name, parameters).

In the case of

commonprefix, being included inos.pathmodule implied to users that the function was meant to be used with paths. - Documentation isn't enough.

commonprefixsurprising behavior was documented since 2002 and this wasn't enough to mitigate future insecure usage two decades later. - Automatic static code analysis and linting tools are likely our best bets at cleaning up widespread footguns like this. An issue was opened with Ruff, a popular code formatter for Python.

I've submitted pull requests that turn the documentation note into an explicit security warning and deprecate the function in Python 3.15. I am hoping that this case can be used as evidence in the future to more rapidly deprecate and replace functions that are confusing or easy to use insecurely on accident.

My work as the Security Developer-in-Residence at the Python Software Foundation is sponsored by Alpha-Omega. Thanks to Alpha-Omega for supporting security in the Python ecosystem.

Discovering the footgun

Earlier this month I published the advisory for CVE-2026-1703, a vulnerability in pip that allows

extremely limited path traversal when unpacking a wheel archive file.

The root-cause for this vulnerability was a function is_within_directory()

that checked whether a target path was within the extraction directory.

Previously the function was implemented like so:

import os

def is_within_directory(directory: str, target: str) -> bool:

"""

Return true if the absolute path of target is within the directory

"""

abs_directory = os.path.abspath(directory)

abs_target = os.path.abspath(target)

prefix = os.path.commonprefix([abs_directory, abs_target])

return prefix == abs_directory

This function was added to pip in 2019.

The function intention is to check whether directory is the prefix

of target, implying that target is within directory.

However, this is not how os.path.commonprefix() works in practice.

commonprefix() compares character-by-character (/..a../..b..),

not using path segments (/a../b..). This subtle difference means

that the function is not safe to use on paths without extra mitigations, like so:

def is_within_directory(directory: str, target: str) -> bool:

...

# By adding a "/" terminator, the character-by-character

# algorithm is now safe to use for directories.

abs_directory = os.path.abspath(directory) + "/"

abs_target = os.path.abspath(target)

prefix = os.path.commonprefix([abs_directory, abs_target])

return prefix == abs_directory

Investigating other usages

Seeing this insecure usage in a critical library like pip signaled to

me that this confusion was not likely to be isolated. There are almost

40K uses of os.path.commonprefix on GitHub alone.

The git blame

on os.path.commonprefix in CPython stalls out at the “initial commit” moving CPython

to git, so we're going to have to start looking at source releases

to see the full history. I also investigated the socializing around

the API to document how the function has been misused and misunderstood

over the years, and in doing so built a case to deprecate and remove

the function.

Python 0.9.1 (1991)

The earliest version of Python source code available on the internet that I know of is for version 0.9.1. Wikipedia

lists this version as being published in February 1991, so ~35 years ago this month.

Looking in lib/path.py we see the earliest implementation of commonprefix()

(with tabs instead of spaces):

# Return the longest prefix of all list elements.

#

def commonprefix(m):

if not m: return ''

prefix = m[0]

for item in m:

for i in range(len(prefix)):

if prefix[:i+1] <> item[:i+1]:

prefix = prefix[:i]

if i = 0: return ''

break

return prefix

This implementation identical to the commonprefix function in current use, and still within a

path-themed module. Note that <> is an alias for !=.

Python 2.0.1 (2000)

The earliest version of Python source code that's available on

the contemporary “Python Source Releases” page is Python 2.0.1.

In this source release in the Lib/posixpath.py we still see commonprefix()

unchanged:

# Return the longest prefix of all list elements.

def commonprefix(m):

"Given a list of pathnames, returns the longest common leading component"

if not m: return ''

prefix = m[0]

for item in m:

for i in range(len(prefix)):

if prefix[:i+1] <> item[:i+1]:

prefix = prefix[:i]

if i == 0: return ''

break

return prefix

First report of confusing behavior (2002)

Armin Rigo emailed the python-dev mailing list in 2002

reporting their surprise at commonprefix() behavior, specifically

noting the module:

“I recently discovered that

os.path.commonprefix(list-of-strings)returns the longest substring that is an initial segment of all the given strings, and that this has nothing to do with the fact that the strings might be paths. I wonder why this has been put inos.pathand not in the string module in the first place. This location misled me for a long time into thinking that commonprefix() would return the longest common *path*”

Michael Hudson replied that they recalled a discussion which “decided that there is no use for such a thing, but that changing [the function] might break code for people who found a use”. Armin’s reply notes that the location of the function is the source of the confusion: “Can't we deprecate the thing and move it elsewhere?”. At this point it was decided to document the unexpected behavior with this warning:

“Note that this may return invalid paths because it works a character at a time.”

This thread also noted that the original intent for the function may

have been to provide the behavior you get on a terminal after partially

typing a path and then hitting TAB to auto-complete, but there wasn't

a definitive answer as to why the function existed in os.path.

“What’s the point of os.path.commonprefix()?” (2010)

Ned Batchelder, maintainer of the popular coverage.py project, published a blog post in 2010 that noted that “the function is worse than useless, it’s misleading” and required patching a bug out of coverage.py as a result. Ned recommended that the documentation warning should explain that the function isn't meant to be used on paths and specifically that “the function is in the wrong place”.

SecureDrop path traversal vulnerability (2013)

SecureDrop, a system deployed by many media organizations for securely accepting whistleblower submissions,

was vulnerable to path traversal due to using os.path.commonprefix()

API incorrectly. This issue was found during a security audit by Cure53.

The confusing behavior and name mismatch wasn't reported upstream to the CPython project.

As far as I know, this is the first known security issue resulting from commonprefix() unexpected behavior.

Python 3.5 (2017)

In 2017 Valentin Lorenz reported to bugs.python.org

that commonprefix still doesn't actually process paths the way users expect,

using characters instead of path segments.

This report led to the addition of a new function, os.path.commonpath(),

which found the common path segment prefix. The function os.path.commonprefix() was not deprecated.

HTTPPasswordMgr security issue (2020, 2022)

Donát Nagy (2020) and later Serhiy Storchaka (2022)

reported an issue in the is_suburi() method for the HTTPPasswordMgr class which used the commonprefix() function

insecurely. Serhiy noted that at the time, this was just one of three

total uses of the os.path.commonprefix() function within the standard library

and that the use was insecure.

Trellix campaign to fix CVE-2007-4559 (2022)

CVE-2007-4559 is a vulnerability in the Python tarfile module

which allowed path traversal during extraction of a malicious tar archive.

A security company Trellix launched a campaign

to mitigate vulnerable

code on GitHub that uses TarFile.extractall() by first checking all tar members

for path traversal. Unfortunately, the filtering function uses os.path.commonprefix()

insecurely, meaning the filtering function itself is also vulnerable path traversal:

def is_within_directory(directory, target):

abs_directory = os.path.abspath(directory)

abs_target = os.path.abspath(target)

prefix = os.path.commonprefix([abs_directory, abs_target])

return prefix == abs_directory

Recognize this function? This function is almost identical to the one used in pip. As far as I can tell, the implementation was copied from pip which was merged in 2019, but not yet discovered to be vulnerable.

According to this GitHub comment, over 61,000 pull requests were submited

with this insecure mitigation for CVE-2007-4559. Searching for the name is_within_directory() in Python files turns

up 2.7K hits. From my own testing none of the os.path.commonprefix() use within top projects on the Python Package Index (PyPI)

are vulnerable, but projects that use the is_within_directory() function provided by Trellix

on GitHub should switch to using os.path.commonpath().

This long history of insecure usage was enough to finally deprecate the function

in favor of os.path.commonpath(). I hope this story can be

evidence that when users report accidentally using functions insecurely that it's

a signal to fix the confusing labeling by renaming or removing the

function in favor of an API designed and labeled appropriately.

Thanks for keeping RSS alive! ♥

February 27, 2026 12:00 AM UTC

February 26, 2026

Real Python

Quiz: Hands-On Python 3 Concurrency With the asyncio Module

This quiz sharpens your intuition for Python’s asyncio module. You’ll decide when async is the right tool, see how the event loop schedules work, and understand how coroutines pause and resume around I/O.

Along the way, you’ll revisit async and await, coroutine creation, async generators, asyncio.run(), and concurrent execution with asyncio.gather(). For a quick refresher before you start, check out Hands-On Python 3 Concurrency With the asyncio Module.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

February 26, 2026 12:00 PM UTC

Graham Dumpleton

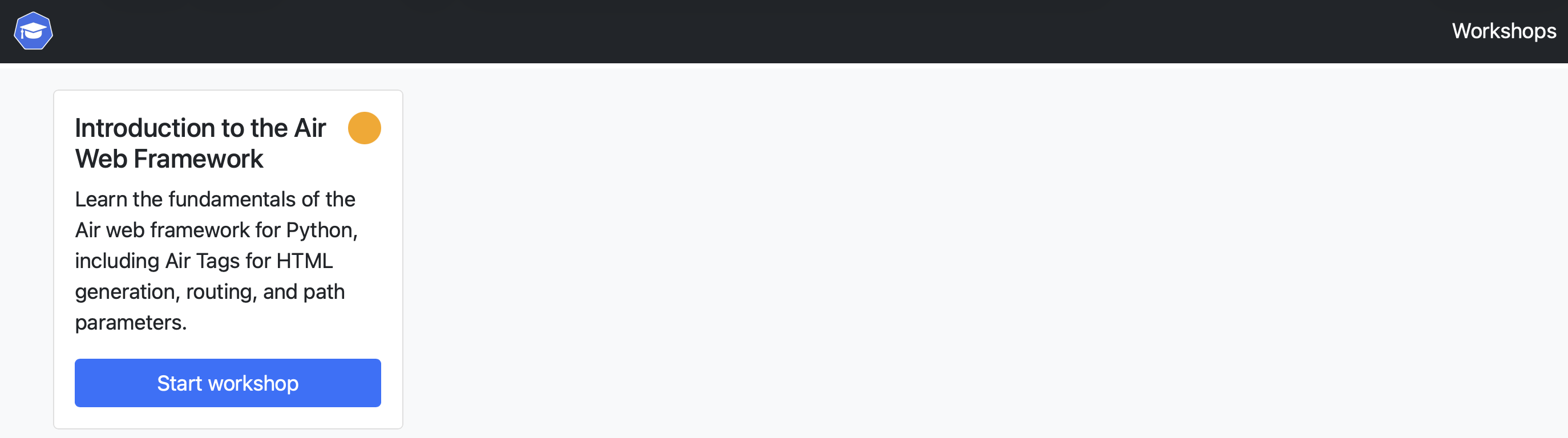

Deploying Educates yourself

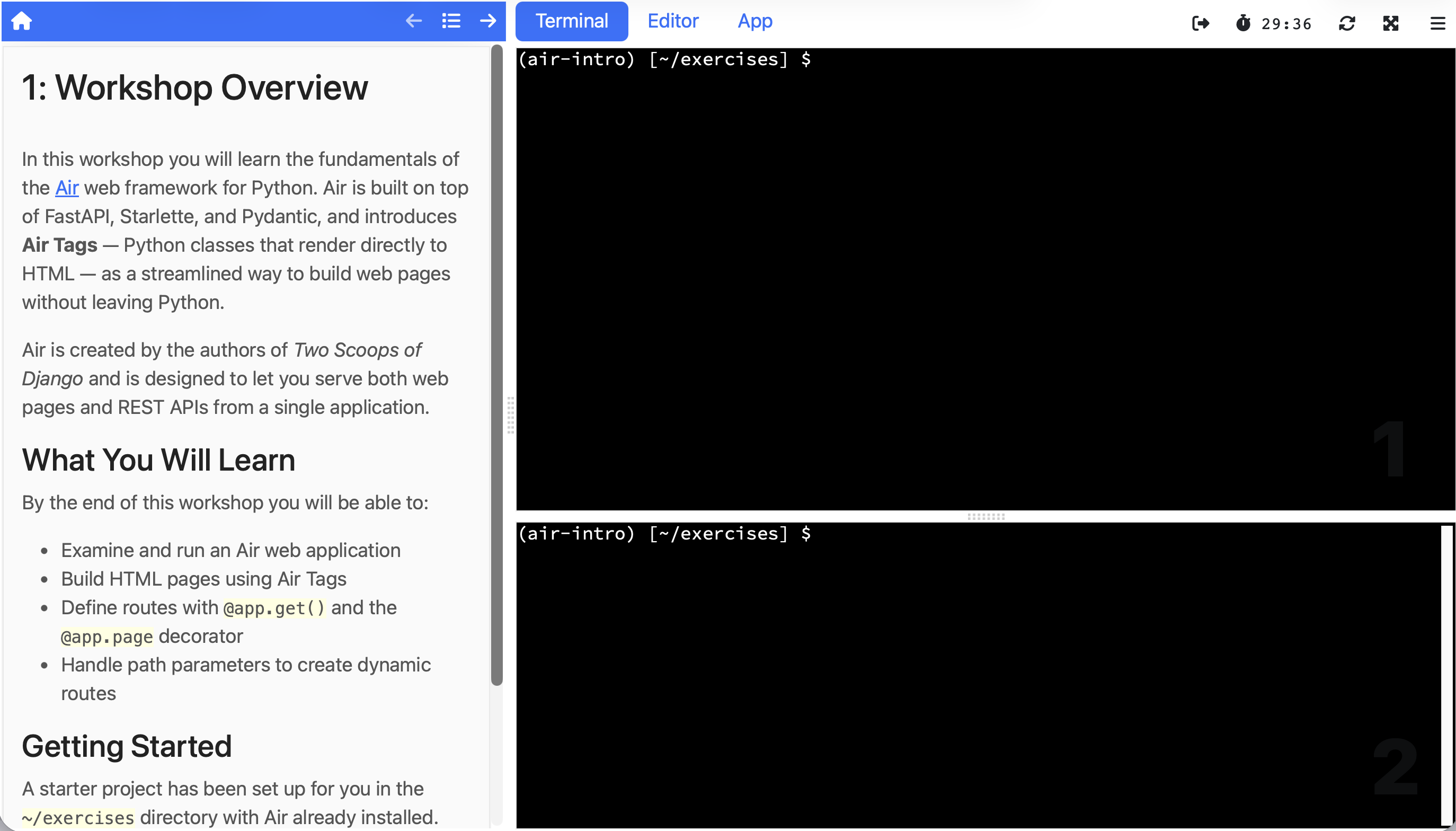

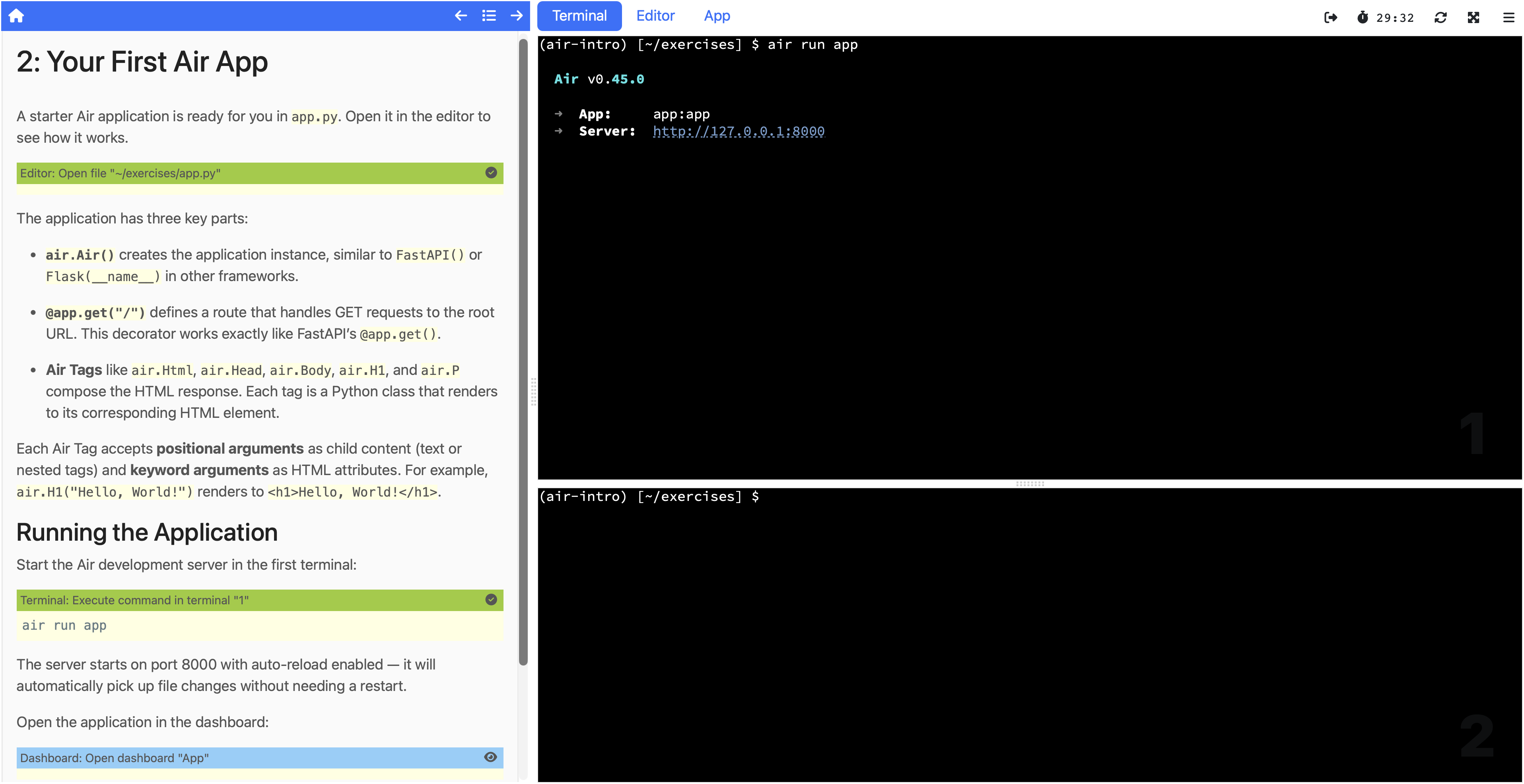

In my last post I showed how an AI skill can generate a complete interactive workshop for the Educates training platform. The result was a working workshop for the Air Python web framework, and you can browse the source in the GitHub repository. But having workshop source files sitting in a repository is only half the story. The question that naturally follows is: how do you actually deploy it?

If you've used platforms like Killercoda, Instruqt, or Strigo, the answer would be straightforward. You push your content to the platform, and it handles the rest. But that convenience comes with a trade-off that's easy to overlook until it bites you.

Not another SaaS platform

The interactive workshop space has been dominated by SaaS offerings. Katacoda was one such option, but when it shut down in 2022, a lot of people lost workshops they'd invested significant time in creating. Killercoda emerged as a successor, but the fundamental dynamic is the same: you're reliant on a third party. Instruqt and Strigo are commercial services where you pay for access and have no control over how the platform evolves, what it costs next year, or whether it continues to exist at all.

Educates takes a different approach. It's open source and self-hosted. You deploy it on your own infrastructure, which means you decide where it runs, when it runs, and who has access. Whether you're running private internal training for your team or hosting public workshops at a conference, you own the platform. If you want to modify how it works, you can. If you want to run it air-gapped inside a corporate network, you can do that too. That freedom is the point.

Deploy it where you want

Because you're deploying Educates yourself, you get to choose the infrastructure. Educates runs on Kubernetes, and that Kubernetes can live anywhere. You could use a managed cluster from a cloud provider like AWS, GCP, or Azure. You could run your own Kubernetes on virtual machines or physical hardware. Or, if you just want to try things out on your own machine, the Educates CLI can create a local Kubernetes cluster for you using Kind running on Docker.

That range of options means you can go from personal experimentation to production training without switching platforms. The same workshop content works regardless of where the cluster is running.

For the rest of this post I'll walk through that local option, since it's the easiest way to get started and doesn't require any cloud infrastructure.

Creating a local Educates environment

The Educates CLI handles the setup. If you have Docker running on your machine, creating a local Educates environment is a single command:

educates create-cluster

This creates a Kind-based Kubernetes cluster and installs everything Educates needs on top of it: the platform operators that manage workshop sessions, a local container image registry, and ingress routing so you can access workshops through your browser. It takes a few minutes to complete, but once it's done you have a fully functional Educates installation running locally.

Publishing and deploying a workshop

With the local environment running, you can publish the Air workshop from a local checkout of the GitHub repository. From the workshop directory, run:

educates publish-workshop

This builds an OCI image containing the workshop files and pushes it to the local image registry that was set up alongside the cluster. The workshop definition file (which the AI skill created as part of the workshop in my previous post) already contains everything Educates needs to know about how to deploy and configure the workshop, so there's nothing else to set up.

To deploy the workshop so it's available to use, run:

educates deploy-workshop

That's it. The workshop is now running on your local Educates installation and ready to be accessed.

Accessing the workshop

To open the training portal in your browser, run:

educates browse-workshops

This opens the Educates training portal, which is where learners go to find and start workshops.

From the portal, you select the workshop you want to run and click to start it. Educates spins up an isolated session for you, and after a moment you're dropped into the workshop dashboard.

The dashboard is the full Educates workshop experience. On one side you have the workshop instructions with their clickable actions. On the other side is the integrated environment with a terminal and editor, plus any additional dashboard tabs the workshop has configured (in this case, a browser tab for viewing the running web application). Everything the learner needs is right there, and it's all running on your own machine.

The workshop I showed being generated in the last post works exactly as expected. You can click through the instructions, run the commands, edit the files, and see the Air web application running in the embedded browser tab. The entire guided experience functions just as it would on a production Educates installation.

Beyond Kubernetes

Running Educates on a local Kubernetes cluster is the most straightforward way to try things out, and it gives you the complete platform experience. But Kubernetes isn't the only option for running a workshop. The same underlying container image used to run the workshop can also be run directly in Docker without any Kubernetes cluster at all. The Educates CLI supports this too.

That said, running in Docker comes with trade-offs. Some features that depend on Kubernetes won't be available, and the workshop itself may need adjustments to work correctly in a Docker environment. I'll cover that in a future post, including how the AI skill from the previous post can help figure out what needs to change.

If you want to try any of this yourself, the Educates documentation has a more detailed quick start guide that covers installation and configuration options beyond what I've shown here.

February 26, 2026 10:38 AM UTC

PyPodcats

Episode 11: With Sheena O'Connell

Learn about Sheena's journey. Sheena is a software engineer with high passion for education. She built an alternative education systems with deep expertise in effective teaching and educator development. She is a founder of Prelude.techLearn about Sheena's journey. Sheena is a software engineer with high passion for education. She built an alternative education systems with deep expertise in effective teaching and educator development. She is a founder of Prelude.tech

We interviewed Sheena O’Connell.

Sheena began her career as a software engineer and technical leader across multiple startups, but her passion for education led her to spend the last five years reimagining how people learn to code professionally. Working within the nonprofit sector, she built alternative education systems from the ground up and developed deep expertise in effective teaching, educator development, and the structural limitations of traditional education models. Sheena is the founder of Prelude.tech, where she delivers rigorous technical training alongside consultation and coaching for technical educators and organizations with education functions. She also leads the Guild of Educators, a community she founded to empower technology educators through shared resources, support, and evidence-based teaching practices.

In this episode, Sheena O’Connell tells us about her journey, the importance of community and good practices for teachers and educators in python, organizational psychology and how herself has become involve in this journey. We talk about how to enable a 10 x team and how to enable the community through guild of educators.

Topic discussed

- Introductions

- Getting to know Sheena

- Her involvement in the community

- Sheena’s journey and her passion for education

- Re-implementing effective education system for learning how to code professionaly in python

- Importance of communiy

- Organizational psychology

- PyCon Africa cool badges

Links from the show

- guild of educators: https://guildofeducators.org/

February 26, 2026 09:00 AM UTC

February 25, 2026

Python Morsels

Lexicographical ordering in Python

Python lexicographically orders tuples, strings, and all other sequences, comparing element-by-element.

String ordering

Is the string "apple" greater than the string "animal"?

>>> "apple" > "animal"

When I ask this question to a roomful of Python developers, I often see folks mouth L-M-N-O-P.

The word "animal" comes before "apple" in alphabetical ordering.

So "apple" is greater than "animal":

>>> "apple" > "animal"

True

Strings in Python are ordered alphabetically. Well, sort of.

Uppercase "Apple" is less than lowercase "apple":

>>> "Apple" < "apple"

True

And we can also order characters that are not in the alphabet.

For example, the dash character (-) is less than the underscore character (_):

>>> '-' < '_'

True

Each character in a Python string has a number associated with it. These numbers are the Unicode code points for these characters:

>>> [ord(c) for c in "apple"]

[97, 112, 112, 108, 101]

>>> [ord(c) for c in "animal"]

[97, 110, 105, 109, 97, 108]

Python essentially uses alphabetical ordering.

But the alphabet it uses consists of every possible character, and the order of those characters comes from their Unicode code points.

I don't recommend memorizing the Unicode code points of each character.

Instead, I would lowercase your strings as you order them. And keep in mind that every character counts when you're ordering strings, even non-alphabetical ones.

Lexicographical ordering

Lexicographical ordering is a fancy …

Read the full article: https://www.pythonmorsels.com/lexicographical-ordering/

February 25, 2026 03:45 PM UTC

Real Python

How to Run Your Python Scripts and Code

Running Python scripts is essential for executing your code. You can run Python scripts from the command line using python script.py, directly by making files executable with shebangs on Unix systems, or through IDEs and code editors. Python also supports interactive execution through the standard REPL for testing code snippets.

This tutorial covers the most common practical approaches for running Python scripts across Windows, Linux, and macOS.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

- The

pythoncommand followed by a script filename executes the code from the command line on all operating systems. - Script mode runs code from files sequentially, while interactive mode uses the REPL for execution and testing with immediate feedback.

- Unix systems require executable permissions and a shebang line like

#!/usr/bin/env python3to run scripts directly as programs. - The

pythoncommand’s-moption runs Python modules by searchingsys.pathrather than requiring file paths. - IDEs like PyCharm and code editors like Visual Studio Code provide built-in options to run scripts from the environment interface.

To get the most out of this tutorial, you should know the basics of working with your operating system’s terminal and file manager. It’d also be beneficial to be familiar with a Python-friendly IDE or code editor and with the standard Python REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop).

Free Download: Get a sample chapter from Python Tricks: The Book that shows you Python’s best practices with simple examples you can apply instantly to write more beautiful + Pythonic code.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “How to Run Your Python Scripts” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

How to Run Your Python ScriptsOne of the most important skills you need to build as a Python developer is to be able to run Python scripts and code. Test your understanding on how good you are with running your code.

What Scripts and Modules Are

In computing, the term script refers to a text file containing a logical sequence of orders that you can run to accomplish a specific task. These orders are typically expressed in a scripting language, which is a programming language that allows you to manipulate, customize, and automate tasks.

Scripting languages are usually interpreted at runtime rather than compiled. So, scripts are typically run by an interpreter, which is responsible for executing each order in a sequence.

Python is an interpreted language. Because of that, Python programs are commonly called scripts. However, this terminology isn’t completely accurate because Python programs can be way more complex than a simple, sequential script.

In general, a file containing executable Python code is called a script—or an entry-point script in more complex applications—which is a common term for a top-level program. On the other hand, a file containing Python code that’s designed to be imported and used from another Python file is called a module.

So, the main difference between a module and a script is that modules store importable code while scripts hold executable code.

Note: Importable code is code that defines something but doesn’t perform a specific action. Some examples include function and class definitions. In contrast, executable code is code that performs specific actions. Some examples include function calls, loops, and conditionals.

In the following sections, you’ll learn how to run Python scripts, programs, and code in general. To kick things off, you’ll start by learning how to run them from your operating system’s command line or terminal.

How to Run Python Scripts From the Command Line

In Python programming, you’ll write programs in plain text files. By convention, files containing Python code use the .py extension, and there’s no distinction between scripts or executable programs and modules. All of them will use the same extension.

Note: On Windows systems, the extension can also be .pyw for those applications that should use the pythonw.exe launcher.

To create a Python script, you can use any Python-friendly code editor or IDE (integrated development environment). To keep moving forward in this tutorial, you’ll need to create a basic script, so fire up your favorite text editor and create a new hello.py file containing the following code:

hello.py

print("Hello, World!")

This is the classic "Hello, World!" program in Python. The executable code consists of a call to the built-in print() function that displays the "Hello, World!" message on your screen.

With this small program in place, you’re ready to learn different ways to run it. You’ll start by running the program from your command line, which is arguably the most commonly used approach to running scripts.

Using the python Command

To run Python scripts with the python command, you need to open a command-line window and type in the word python followed by the path to your target script:

Read the full article at https://realpython.com/run-python-scripts/ »

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

February 25, 2026 02:00 PM UTC

February 24, 2026

Django Weblog

Google Summer of Code 2026 with Django

When we learned that the Django Software Foundation has been accepted as a mentoring organization for Google Summer of Code 2026, it marked another steady milestone in a long-standing relationship. Django first participated in GSoC in 2006, and 2026 represents our 21st consecutive year in the program.

Over two decades, GSoC has become a consistent pathway for contributors to engage more deeply with Django — not just through a summer project, but often through continued involvement that extends well beyond the official coding period.

For many of you reading this, this might be your first exposure to how Django’s open source ecosystem works. So before we get into applications and expectations, let’s take a step back and understand the environment you’re stepping into.

Understanding the Django Ecosystem

The Django Software Foundation (DSF) is the non-profit organization that supports the long-term sustainability of Django. Django itself is developed entirely in the open. Feature discussions, architectural debates, bug reports, design proposals, and code reviews all happen publicly.

That openness is intentional. It allows anyone, from anywhere in the world, to participate. But it also means decisions are rarely made quickly or casually. Changes are discussed carefully. Trade-offs are evaluated. Backwards compatibility is taken seriously.

If you are new, it helps to understand the main spaces where this work happens:

- The Django Forum is where broader discussions take place — new feature ideas, design direction, and community conversations.

- Django Trac is the issue tracker, where bugs, feature requests, and patches are formally recorded and reviewed. If no one is working on an issue, you can assign it yourself and start working on it.

- Code contributions happen through pull requests, where proposed changes are reviewed, tested, and discussed in detail before being merged.

- New features are proposed and discussed in the new-features repository. There is a project board view that shows the state of each proposal.

For someone new, this ecosystem can feel overwhelming at first. Threads may reference decisions made years ago. Review comments can be detailed. Standards are high.

That is precisely why GSoC matters to us. It provides a structured entry point into this culture, with mentorship and guidance along the way, helping contributors understand not just how to write code — but how Django evolves.

Why the Django Forum Is Central

Most GSoC journeys in Django begin on the Django Forum — the community’s public space for technical discussions about features, design decisions, and improvements to Django.

Introducing yourself there is not a formality; it is often your first real contribution. When you discuss a project idea publicly, you demonstrate how you think, how you respond to feedback, and how you handle technical trade-offs. Questions and challenges from mentors are not barriers — they are part of the collaborative design process.

Proposals that grow through open discussion on the Forum are almost always stronger than those written in isolation.

What To Do

If you are planning to apply for GSoC 2026 with Django, here is what we strongly encourage:

Start early.

Do not wait until the application window opens. Begin discussions well in advance.

Engage publicly.

Introduce yourself on the Forum. Participate in ongoing threads. Show consistent involvement rather than one-time activity.

Demonstrate understanding(very important)

Read related tickets and past discussions. Reference them in your proposal. Show that you understand the technical and philosophical context.

Be realistic about scope.

Ambitious ideas are welcome, but they must be grounded in technical feasibility within the GSoC timeframe.

Show iteration.

If your proposal evolves because of feedback, that is a positive signal. It shows adaptability and thoughtful engagement.

What Not To Do

Equally important are the expectations around what we will not consider.

Do not submit a proposal without prior discussion.

A proposal that appears for the first time in the application form, without any Forum engagement, will be at a disadvantage.

Do not generate a proposal using AI and submit it as-is.

If a proposal is clearly AI-generated, lacks discussion history, and shows no evidence of personal understanding, it will be rejected. We evaluate your reasoning process, not just the surface quality of the document.

Do not copy previous proposals.

Each year’s context is different. We expect original thinking and up-to-date understanding.

Do not treat GSoC as a solo internship.

Django development is collaborative. If you are uncomfortable discussing ideas publicly or receiving detailed feedback, this may not be the right fit.

Do not submit empty or placeholder proposal documents.

In previous years, we have received blank or near-empty submissions, which create unnecessary effort for volunteer reviewers. Such proposals will not be considered.

Do not repeatedly tag or ping maintainers for reviews.

Once you’ve submitted your proposal or patch, give reviewers time to respond. Maintainers are volunteers managing many responsibilities, and repeated tagging does not speed up the process. Patience and respectful follow-ups (after a reasonable interval) are appreciated.

On AI Usage

We recognize that AI tools are now part of many developers’ workflows. Using AI to explore documentation, clarify syntax, or organize thoughts is not inherently a problem.

However, AI must not replace ownership.

You should be able to clearly explain your architectural decisions, justify trade-offs, and respond thoughtfully when challenged. If you cannot defend your own proposal without external assistance, it signals a lack of readiness for this kind of work.

The quality we look for is not perfect language — it is depth of understanding.

I’m a First-Time Contributor to Django — What Should I Do?

If this is your first time contributing to Django, start simple and start early.

First, spend some time understanding how Django works as an open source project. Read a few recent discussions on the Django Forum and browse open tickets to see the kinds of problems being discussed.

Next, introduce yourself on the Forum. Share your background briefly and mention what areas interest you. You don’t need to have a perfect project idea on day one — curiosity and willingness to learn matter more.

Then:

- Read the official first time contributor guide carefully.

- Try setting up Django locally and run the test suite.

- Look for small tickets on trac (including documentation or cleanup tasks) to understand the workflow.

- Ask questions on the Forum or in Discord if something is unclear.

Most importantly, be patient with yourself. Django is a mature and widely used framework, and it takes time to understand its design principles and contribution standards.

Strong contributors are not the ones who know everything at the start — they are the ones who show up consistently, engage thoughtfully, and improve through feedback.

To conclude

We are excited to welcome a new group of contributors into the Django ecosystem through Google Summer of Code 2026. We look forward to thoughtful ideas, constructive discussions, and a summer of meaningful collaboration — built not just on code, but on understanding and shared responsibility.

February 24, 2026 09:58 PM UTC

PyCoder’s Weekly

Issue #723: Chained Assignment, Great Tables, Docstrings, and More (Feb. 24, 2026)

#723 – FEBRUARY 24, 2026

View in Browser »

Chained Assignment in Python Bytecode

When doing chained assignment with mutables (e.g. a == b == []) all chained values get assigned to a single mutable object. This article explains why this happens and what you can do instead.

ROHAN PRINJA

Great Tables: Publication-Ready Tables From DataFrames

Learn how to create publication-ready tables from Pandas and Polars DataFrames using Great Tables. Format currencies, add sparklines, apply conditional styling, and export to PNG.

CODECUT.AI • Shared by Khuyen Tran

Replay: Where Developers Build Reliable AI

Replay is a practical conference for developers building real systems. The Python AI & versioning workshop covers durable AI agents, safe workflow evolution, and production-ready deployment techniques. Use code PYCODER75 for 75% off your ticket →

TEMPORAL sponsor

Write Python Docstrings Effectively

Learn to write clear, effective Python docstrings using best practices, common styles, and built-in conventions for your code.

REAL PYTHON course

Discussions

Python Jobs

Python + AI Content Specialist (Anywhere)

Software Engineer (Python / Django) (South San Francisco, CA, USA)

Articles & Tutorials

Join the Python Security Response Team!

The Python Security Response Team is a group of volunteers and PSF staff that coordinate and triage vulnerability reports and remediations. It is governed in a similar fashion to the core team. This article explains what the PSRT is and how you can join.

CPYTHON DEV BLOG

A CLI to Fight GitHub Spam

Hugo is a core Python maintainer and the CPython project gets lots of garbage PRs, not just AI slop but spam tickets as well. To help with this he has written a new GitHub CLI extension that makes it easier to apply a label to the PR and close it.

HUGO VAN KEMENADE

B2B MCP Auth Support

Your users are asking if they can connect their AI agent to your product, but you want to make sure they can do it safely and securely. PropelAuth makes that possible →

PROPELAUTH sponsor

Exploring MCP Apps & Adding Interactive UIs to Clients

How can you move your MCP tools beyond plain text? How do you add interactive UI components directly inside chat conversations? This week on the show, Den Delimarsky from Anthropic joins us to discuss MCP Apps and interactive UIs in MCP.

REAL PYTHON podcast

How to Use Overloaded Signatures in Python?

Sometimes a function takes multiple arguments of different types, and the return type depends on specific combinations of inputs. How do you tell the type checker? Use the @overload decorator from the typing module.

BORUTZKI

icu4py: Bindings to the Unicode ICU Library

The International Components for Unicode (ICU) is the official library for Unicode and globalization tools and is used by many major projects. icu4py is a first step at a Python binding to the C++ API.

ADAM JOHNSON

Evolving Git for the Next Decade

This article summarizes Patrick Steinhardt’s talk at FOSDEM 2026 that discusses the current shortcomings of git and how they’re being addressed, preparing your favorite repo tool for the next decade.

JOE BROCKMEIER

How to Install Python on Your System: A Guide

Learn how to install the latest Python version on Windows, macOS, and Linux. Check your version and choose the best installation method for your system.

REAL PYTHON

TinyDB: A Lightweight JSON Database for Small Projects

If you’re looking for a JSON document-oriented database that requires no configuration for your Python project, TinyDB could be exactly what you need.

REAL PYTHON

Django ORM Standalone: Querying an Existing Database

A practical step-by-step guide to using Django ORM in standalone mode to connect to and query an existing database using inspectdb.

PAOLO MELCHIORRE

Projects & Code

Events

Weekly Real Python Office Hours Q&A (Virtual)

February 25, 2026

REALPYTHON.COM

MLOps Open Source Sprint

February 27, 2026

MEETUP.COM

Melbourne Python Users Group, Australia

March 2, 2026

J.MP

PyBodensee Monthly Meetup

March 2, 2026

PYBODENSEE.COM

Python Unplugged on PyTV

March 4 to March 5, 2026

JETBRAINS.COM

Happy Pythoning!

This was PyCoder’s Weekly Issue #723.

View in Browser »

[ Subscribe to 🐍 PyCoder’s Weekly 💌 – Get the best Python news, articles, and tutorials delivered to your inbox once a week >> Click here to learn more ]

February 24, 2026 07:30 PM UTC

Real Python

Start Building With FastAPI

FastAPI is a web framework for building APIs with Python. It leverages standard Python type hints to provide automatic validation, serialization, and interactive documentation. When you’re deciding between Python web frameworks, FastAPI stands out for its speed, developer experience, and built-in features that reduce boilerplate code for API development:

| Use Case | Pick FastAPI | Pick Flask or Django |

|---|---|---|

| You want to build an API-driven web app | ✅ | — |

| You need a full-stack web framework | — | ✅ |

| You value automatic API documentation | ✅ | — |

Whether you’re building a minimal REST API or a complex backend service, understanding core features of FastAPI will help you make an informed decision about adopting it for your projects. To get the most from this video course, you’ll benefit from having basic knowledge of Python functions, HTTP concepts, and JSON handling.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

February 24, 2026 02:00 PM UTC

The Python Coding Stack

“Python’s Plumbing” Is Not As Flashy as “Magic Methods” • But Is It Better?

You’ve heard this phrase before: “Everything is an object in Python”. But here’s another phrase that’s related but rather less catchy:

Everything goes through special methods (dunder methods) in Python

Special methods are everywhere. However, you don’t see them. In fact, you’re not meant to use them directly unless you’re defining them within a class. They’re out of sight. But they keep everything moving smoothly in Python.

Here’s a short essay exploring where these special methods fit within Python.

Why Should I Care About Special Methods?

“Everything goes through special methods in Python.” I should probably preface the phrase with “almost”, but the phrase is already unwieldy as it is.

You want to display an object on the screen? Python looks for guidance in .__str__() or .__repr__().

You want to use the object in a for loop? Is it even possible? Python looks for .__iter__() to check whether it can iterate over the object and how.

Do you want to fetch an individual item from the object? If this makes sense for this object, then it will have a .__getitem__() special method.

How should Python interpret an object’s truthiness? There’s .__bool__() for that. Or .__len__()!

Ah, you’d like to add an object to another object. Does your object have a .__add__() special method?

I could go on. I’ll post links to articles that cover some of these special methods in more detail below.

I’m also running a two-hour workshop this Thursday, 26 February, called Python’s Plumbing • Dunder Methods and Python’s Hidden Interface

Many operations you take for granted in your code are governed by special methods. Each class defines the special methods it needs, and Python knows how to handle instances of that class through those methods.

But let’s talk about different ways we refer to these special methods.

What’s In A Name?

These methods are called special methods. That’s their official name. These special methods have double underscores at the beginning and end of their names, such as .__init__(), .__str__(), and .__iter__(). This double-underscore notation led to the informal name “dunder methods”. And let’s face it, most people call them “dunder methods” instead of their actual name: “special methods.”

I often call them dunder methods, too. However, the term dunder merely describes the syntax, double underscore, so it doesn’t tell us much about what they do. The term special doesn’t tell us what they do, either, but it shows us they have a special role in Python.

There’s No Such Thing as Magic

Some people also call them magic methods. However, I avoid this term, and I discourage students from using it. It makes these methods look unnecessarily mysterious, perhaps difficult to understand because it’s all down to magic.

But there’s no such thing as magic (unless you’re Harry Potter). And the magic tricks we see from real-world “magicians” are just that – tricks. The magic dissolves away once you know how the trick works.

And if you’re learning Python, then you need to learn how to be a magician. You need to learn the “magic tricks.” Therefore, they’re no longer magic!

Python’s Plumbing (”Plumbing Methods”, Anyone?)

So, “special method” tells us that these methods are important, but it doesn’t tell us what they do. “Dunder method” describes the syntax. “Magic method” misleads us and doesn’t provide any useful insight.

How about “plumbing methods” then? Now, before anyone takes me too seriously, I’m saying this with my tongue firmly in my cheek. I’m not that foolish to suggest a new term for the whole Python community to adopt. And it’s not as flashy as “magic methods” or as cool as “dunder methods”. But bear with me…

Let’s explore the analogy, even if the term won’t catch on.

Disclaimer: I know very little about plumbing. But I think that’s OK for this essay!

There are pipes, valves, and other stuff carrying water (clean or otherwise) around your house. You know they’re there. You need them there. But you don’t see them.

You don’t think about these pipes unless you’re building the house – or unless the pipes are blocked or leaking.

The house’s plumbing keeps things running smoothly. Yet, it’s out of sight, and you don’t normally think about it. You take it for granted.

You see where I’m going, right?

Python’s special methods perform the same role. You don’t normally see them when coding since they’re called implicitly, behind the scenes. You do need to define the special methods you need when you’re defining the class, just like you’ll need to lay the pipes when building or modifying your house.

And if something goes wrong in your code, you may need to dive into how these dunder methods behave, just as when you have a leak and need to explore which pipe is responsible.

Good plumbing is reliable, predictable. Bad plumbing is asking for trouble. The same applies to the infrastructure you create through the special methods you define in classes.

So, there you go, they’re “plumbing methods”. This name tells us what they do!

I’m running a two-hour live workshop this Thursday called Python’s Plumbing • Dunder Methods and Python’s Hidden Interface. This is your last chance to join and I may not run this workshop again for a while.

This workshop is the first of three in the Python Behind the Scenes series. The other two workshops in the series are:

#2 • Pythonic Iteration: Iterables, Iterators,

itertools#3 • To Inherit or Not? Inheritance, Composition, Abstract Base Classes, and Protocols

Join all three, or pick and choose:

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

For more Python resources, you can also visit Real Python—you may even stumble on one of my own articles or courses there!

Also, are you interested in technical writing? You’d like to make your own writing more narrative, more engaging, more memorable? Have a look at Breaking the Rules.

And you can find out more about me at stephengruppetta.com

Further reading related to this article’s topic:

This is part of a longer OOP series: Time for Something Special • Special Methods in Python Classes

The Manor House, the Oak-Panelled Library, the Vending Machine, and Python’s __getitem__() [Part 1]

Why Do 5 + “5” and “5” + 5 Give Different Errors in Python? • Do You Know The Whole Story?

February 24, 2026 01:56 PM UTC

PyBites

Why do we insist on struggling alone?

A realisation about my son’s basketball team reminded me that we should never be ashamed to ask for help, or better yet, seek formal coaching/support.

Last year, for two straight seasons, my son’s team got absolutely smashed on the court.

They had the energy and the determination, but they were effectively running in circles without any real guidance (and I’m definitely not a basketball player!).

Sound familiar? It should!

It’s exactly what it feels like when you can’t figure out where you’re going wrong, stuck in tutorial hell or banging your head against a wall trying to architect an application by yourself.

You end up spending hours debugging something a senior developer could easily point out in a 5-minute PR review. To put it another way – you’re wasting the most valuable resource you have: your time.

Everything changed for my son’s team when we brought in an experienced coach to help. He analysed their play style, identified each of their strengths and gaps, then gave them proven, concrete steps to correct their form. They just finished their latest season in first place.

This is the exact strategy behind the Pybites Developer Mindset (PDM) program. PDM is a 12-week personalised 1:1 coaching program focused on project-based development, designed to bridge specific gaps in an individual’s knowledge. This is bespoke coaching to help you where you need it.

We provide detailed, actionable PR reviews to speed up the learning process. You’ll learn to navigate real-world constraints that go beyond your code, like hosting, deployment and stakeholder needs.

Stop guessing and start building with a mentor who will reinforce professional developer skills and validate your technical direction.

You can use the links below to chat with us about how we can best help. There really is no need to go it alone!

Julian

This was originally sent to our email list. Join here.

And if you do decide to go alone…

February 24, 2026 03:36 AM UTC

Seth Michael Larson

Respecting maintainer time should be in security policies

Generative AI tools becoming more common means that vulnerability reports these days are loooong. If you're an open source maintainer, you unfortunately know what I'm talking about. Markdown-formatted, more than five headings, similar in length to a blog post, and characterized as a vulnerability worthy of its own domain name.

This makes triaging vulnerabilities by often under-resourced maintainer more difficult, time-consuming, and stressful. Whether a report is a genuine vulnerability or not, it now requires more time from maintainers to make a determination than is necessary. I've heard from multiple maintainers how specifically report length weighs negatively on maintainer time, whether these are “slop vulnerability reports” or just overly-thorough reporters.

David Lord, the maintainer of Flask and Pallets, captures this problem concisely, that the best security reports respect maintainer time:

Post by @davidism@mas.toView on Mastodon

Here's my proposal: require security reports respect maintainer time in your security policy. This especially applies to “initial” security reports, where the reporter is most likely to send disproportionately more information than is needed to make an initial determination.

The best part about this framing is you don't have to mention the elephant in the room. Here's a few example security policy requirements to include:

- Initial reports must be six or fewer sentences describing the issue and optionally a short proof-of-concept script. Follow-ups may be longer if the initial report is deemed a vulnerability.

- Initial reports must not contain a severity (such as: "critical") or CVSS score. This calculation will be completed after the report is accepted by maintainers.

- Reports must not make a determination whether a behavior of the software represents a vulnerability.

Notice I didn't even have to mention LLMs or generative AI, so there’s no ambiguity about whether a given report follows the policy or not. While you have reporters reading your security policy, you might also add suggestions that also benefit maintainers remediating vulnerabilities faster:

- If applicable, submitting a patch or an expected behavior along with a proof-of-concept makes remediating a vulnerability easier.

- We appreciate vulnerability reporters that are willing to review patches prior to publication.

- If you would like to be credited as a reporter, please mention that in your report.

After this is added to a project security policy (preferably under its own linkable heading) then any security report that doesn't respect maintainer time can be punted back to the reporter with a canned response:

Your report doesn't meet our security policy: https://... Please amend your report to meet our policy so we may efficiently make a determination and remediation. Thank you!

Now your expectations have been made clear to reporters and valuable maintainer time is saved. From here the security report can evolve more like a dialogue which requires maintainer time and energy proportionate to the value that the report represents to the project.

I understand this runs counter to how many vulnerability teams work today. Many reporters opt to provide as much context and detail up-front in a single report, likely to reduce back-and-forth or push-back from projects. If teams reporting vulnerabilities to open source projects want to be the most effective, they should meet the pace and style that best suites the project they are reporting to.

Please note that many vulnerability reporters are acting in good faith and aren't trying to burden maintainers. If you believe your peer is acting in good faith, maybe give them a pass if the report doesn't strictly meet the requirements and save the canned response for the bigger offenders.

Have any thoughts about this topic? Have you seen this in any open source security policies already? Let me know! Thanks to OSTIF founder Derek Zimmer for reviewing this blog post prior to publication.

Thanks for keeping RSS alive! ♥

February 24, 2026 12:00 AM UTC

Python⇒Speed

Unit testing your code's performance, part 2: Catching speed changes

In a previous post I talked about unit testing for speed, and in particular testing for big-O scalability. The next step is catching cases where you’ve changed not the scalability, but the direct efficiency of your code.

If your first thought is “how this is different from running benchmarks?”, well, good point! An excellent starting point for performance is implementing a benchmark that runs automatically in CI, on every single pull request. If you haven’t got that, you probably want to go do that first.

Once you have implemented CI benchmarks, they will typically run when you submit a pull request or the equivalent. And if you’re doing performance work, that’s hopefully just a formality, as you likely have been benchmarking your code locally as you work.

But what happens when you or a colleague are working on features or bugfixes, and accidentally modify a performance-critical code path? You make changes, run the tests locally, run a linter, open a pull request… and now the benchmark runs, and tells you that your code has made things slower. This is annoying, because now you have to go back and figure out which specific change was the cause.

So what you really want is to get some sense of whether performance changed much earlier in the process, giving you immediate feedback when you’re running tests locally. Since a reliable benchmark environment is hard, switching to a test might allow for an early warning.

Read more...February 24, 2026 12:00 AM UTC

Israel Fruchter

Coodie: A 4-year-old idea brought to life by AI (and some coffee)

So, let’s rewind a bit. About four years ago, I was looking at Beanie — this really nifty, Pydantic-based ODM for MongoDB. And as someone who spends an unhealthy amount of time deep in the trenches of ScyllaDB and Cassandra, I had a thought: “Where is my Beanie? I want a hoodie, but for Cassandra.” And thus, the name was born: coodie = cassandra + beanie (hoodie). Catchy, right?

Like any respectable developer, I rushed to GitHub, created the repository fruch/coodie, maybe wrote a highly ambitious README.md, set up a pyproject.toml, and then… absolutely nothing. Crickets. Life happened. I had CI pipelines to fix, Scylla drivers to maintain, conferences like PyConIL and EuroPython to attend, and live-tweeting to do. coodie just sat there, gathering digital dust, a glorious monument to my good intentions and severe lack of free time.

Fast forward to today. The AI era.

We are living in a weird timeline where LLMs are everywhere, threatening to take our jobs while simultaneously failing to center a div. People are talking about AI coding assistants non-stop. I myself was quite happy with my usual workflow, but I figured — why not take my 4-year-old fever dream for a walk in the park and feed it to the machine?

I threw the basic concept at an AI. I gave it some ground rules: it has to use Pydantic v2, it needs to be backed by scylla-driver, and it needs to feel as magical as Beanie.

And holy crap. It actually worked.

I spent four years procrastinating on this, and a glorified autocomplete bot basically bootstrapped the whole thing while I was sipping my morning coffee. I’m not sure if I should be proud of my newfound status as a “prompt engineer,” or slightly terrified that my open-source street cred is now partially owned by a matrix of weights and biases.

The sweet setup we have now

Despite the AI doing the heavy lifting, the architecture actually makes a lot of sense. Here is what coodie brings to the table:

- Pydantic v2 all the way: Define your documents with full type-checking support.

- Declarative schemas: You just annotate fields with

PrimaryKey,ClusteringKey,Indexed, orCounter. - Automatic table management: You call

sync_table()and it creates or evolves the table idempotently. No more writing raw CQL just to add a column. - Sync and Async APIs: Because why choose? You can use

coodie.aioif you are riding the asyncio train, orcoodie.syncif you want blocking code. - Chainable QuerySets: Doing

await Product.find(brand="Acme").limit(10).all()just feels right.

Here is a quick taste of what the AI and I managed to cook up:

from typing import Annotated

from uuid import UUID, uuid4

from pydantic import Field

from coodie import Document, init_coodie, PrimaryKey

class Product(Document):

id: Annotated[UUID, PrimaryKey()] = Field(default_factory=uuid4)

name: str

price: float = 0.0

class Settings:

keyspace = "my_ks"

And then querying it is a breeze:

# async

products = (

await Product.find()

.filter(brand="Acme")

.order_by("price")

.limit(20)

.all()

)

Wrapping up

The AI works out of the box with almost zero friction. It’s very impressive, and honestly, a bit surreal to see an idea you abandoned years ago suddenly have a passing CI suite, complete with tests and GitHub Actions (which are still very tidy to look at, by the way).

You can check out the code, star it, or fork it over at github.com/fruch/coodie.

PRs are welcome. Preferably written by humans, but honestly… I guess I can’t really enforce that anymore, can I? יאללה, let’s see how it goes.

February 24, 2026 12:00 AM UTC

February 23, 2026

Anarcat

PSA: North america changes time forward soon, Europe next

This is a copy of an email I used to send internally at work and now made public. I'm not sure I'll make a habit of posting it here, especially not twice a year, unless people really like it. Right now, it's mostly here to keep with my current writing spree going.

This is your bi-yearly reminder that time is changing soon!

What's happening?

For people not on tor-internal, you should know that I've been sending semi-regular announcements when daylight saving changes occur. Starting now, I'm making those announcements public so they can be shared with the wider community because, after all, this affects everyone (kind of).

For those of you lucky enough to have no idea what I'm talking about, you should know that some places in the world implement what is called Daylight saving time or DST.

Normally, you shouldn't have to do anything: computers automatically change time following local rules, assuming they are correctly configured, provided recent updates have been applied in the case of a recent change in said rules (because yes, this happens).

Appliances, of course, will likely not change time and will need to adjusted unless they are so-called "smart" (also known as "part of a bot net").

If your clock is flashing "0:00" or "12:00", you have no action to take, congratulations on having the right time once or twice a day.

If you haven't changed those clocks in six months, congratulations, they will be accurate again!

In any case, you should still consider DST because it might affect some of your meeting schedules, particularly if you set up a new meeting schedule in the last 6 months and forgot to consider this change.

If your location does not have DST

Properly scheduled meetings affecting multiple time zones are set in UTC time, which does not change. So if your location does not observer time changes, your (local!) meeting time will not change.

But be aware that some other folks attending your meeting might have the DST bug and their meeting times will change. They might miss entire meetings or arrive late as you frantically ping them over IRC, Matrix, Signal, SMS, Ricochet, Mattermost, SimpleX, Whatsapp, Discord, Slack, Wechat, Snapchat, Telegram, XMPP, Briar, Zulip, RocketChat, DeltaChat, talk(1), write(1), actual telegrams, Meshtastic, Meshcore, Reticulum, APRS, snail mail, and, finally, flying a remote presence drone to their house, asking what's going on.

(Sorry if I forgot your preferred messaging client here, I tried my best.)

Be kind; those poor folks might be more sleep deprived as DST steals one hour of sleep from them on the night that implements the change.

If you do observe DST

If you are affected by the DST bug, your local meeting times will change access the board. Normally, you can trust that your meetings are scheduled to take this change into account and the new time should still be reasonable.

Trust, but verify; make sure the new times are adequate and there are no scheduling conflicts.

Do this now: take a look at your calendar in two week and in April. See if any meeting need to be rescheduled because of an impossible or conflicting time.

When does time change, how and where?

Notice how I mentioned "North America" in the subject? That's a lie. ("The doctor lies", as they say on the BBC.) Other places, including Europe, also changes times, just not all at once (and not all North America).

We'll get into "where" soon, but first let's look at the "how". As you might already know, the trick is:

Spring forward, fall backwards.

This northern-centric (sorry!) proverb says that clocks will move forward by an hour this "spring", after moving backwards last "fall". This is why we lose an hour of work, sorry, sleep. It sucks, to put it bluntly. I want it to stop and will keep writing those advisories until it does.

To see where and when, we, unfortunately, still need to go into politics.

USA and Canada

First, we start with "North America" which, really, is just some parts of USA[1] and Canada[2]. As usual, on the Second Sunday in March (the 8th) at 02:00 local (not UTC!), the clocks will move forward.

This means that properly set clocks will flip from 1:59 to 3:00, coldly depriving us from an hour of sleep that was perniciously granted 6 months ago and making calendar software stupidly hard to write.

Practically, set your wrist watch and alarm clocks[3] back one hour before going to bed and go to bed early.

[1] except Arizona (except the Navajo nation), US territories, and Hawaii

[2] except Yukon, most of Saskatchewan, and parts of British Columbia (northeast), one island in Nunavut (Southampton Island), one town in Ontario (Atikokan) and small parts of Quebec (Le Golfe-du-Saint-Laurent), a list which I keep recopying because I find it just so amazing how chaotic it is. When your clock has its own Wikipedia page, you know something is wrong.

[3] hopefully not managed by a botnet, otherwise kindly ask your bot net operator to apply proper software upgrades in a timely manner

Europe

Next we look at our dear Europe, which will change time on the last Sunday in March (the 29th) at 01:00 UTC (not local!). I think it means that, Amsterdam-time, the clocks will flip from 1:59 to 3:00 AM local on that night.

(Every time I write this, I have doubts. I would welcome independent confirmation from night owls that observe that funky behavior experimentally.)

Just like your poor fellows out west, just fix your old-school clocks before going to bed, and go to sleep early, it's good for you.

Rest of the world with DST

Renewed and recurring apologies again to the people of Cuba, Mexico, Moldova, Israel, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Chile (except Magallanes Region), parts of Australia, and New Zealand which all have their own individual DST rules, omitted here for brevity.

In general, changes also happen in March, but either on different times or different days, except in the south hemisphere, where they happen in April.

Rest of the world without DST

All of you other folks without DST, rejoice! Thank you for reminding us how manage calendars and clocks normally. Sometimes, doing nothing is precisely the right thing to do. You're an inspiration for us all.

Changes since last time

There were, again, no changes since last year on daylight savings that I'm aware of. It seems the US congress debating switching to a "half-daylight" time zone which is an half-baked idea that I should have expected from the current USA politics.

The plan is to, say, switch from "Eastern is UTC-4 in the summer" to "Eastern is UTC-4.5". The bill also proposes to do this 90 days after enactment, which is dangerously optimistic about our capacity at deploying any significant change in human society.

In general, I rely on the Wikipedia time nerds for this and Paul Eggert which seems to singlehandledly be keeping everything in order for all of us, on the tz-announce mailing list.

This time, I've also looked at the tz mailing list which is where I learned about the congress bill.

If your country has changed time and no one above noticed, now would be an extremely late time to do something about this, typically writing to the above list. (Incredibly, I need to write to the list because of this post.)

One thing that did change since last year is that I've implemented what I hope to be a robust calendar for this, which was surprisingly tricky.

If you have access to our Nextcloud, it should be visible under the heading "Daylight saving times". If you don't, you can access it using this direct link.

The procedures around how this calendar was created, how this email was written, and curses found along the way, are also documented in this wiki page, if someone ever needs to pick up the Time Lord duty.

February 23, 2026 07:31 PM UTC

Real Python

Python for Loops: The Pythonic Way

Python’s for loop allows you to iterate over the items in a collection, such as lists, tuples, strings, and dictionaries. The for loop syntax declares a loop variable that takes each item from the collection in each iteration. This loop is ideal for repeatedly executing a block of code on each item in the collection. You can also tweak for loops further with features like break, continue, and else.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

- Python’s

forloop iterates over items in a data collection, allowing you to execute code for each item. - To iterate from

0to10, you use thefor index in range(11):construct. - To repeat code a number of times without processing the data of an iterable, use the

for _ in range(times):construct. - To do index-based iteration, you can use

for index, value in enumerate(iterable):to access both index and item.

In this tutorial, you’ll gain practical knowledge of using for loops to traverse various collections and learn Pythonic looping techniques. You’ll also learn how to handle exceptions and use asynchronous iterations to make your Python code more robust and efficient.

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free sample code that shows you how to use for loops in Python.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “Python for Loops: The Pythonic Way” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

Python for Loops: The Pythonic WayIn this quiz, you'll test your understanding of Python's for loop. You'll revisit how to iterate over items in a data collection, how to use range() for a predefined number of iterations, and how to use enumerate() for index-based iteration.

Getting Started With the Python for Loop

In programming, loops are control flow statements that allow you to repeat a given set of operations a number of times. In practice, you’ll find two main types of loops:

forloops are mostly used to iterate a known number of times, which is common when you’re processing data collections with a specific number of data items.whileloops are commonly used to iterate an unknown number of times, which is useful when the number of iterations depends on a given condition.

Python has both of these loops and in this tutorial, you’ll learn about for loops. In Python, you’ll generally use for loops when you need to iterate over the items in a data collection. This type of loop lets you traverse different data collections and run a specific group of statements on or with each item in the input collection.