Planet Python

Last update: February 23, 2026 07:46 AM UTC

February 23, 2026

Tibo Beijen

Introducing the Zen of DevOps

Introduction Over the past ten years or so, my role has gradually shifted from software to platforms. More towards the ‘ops’ side of things, but coming from a background that values APIs, automation, artifacts and guardrails in the form of automated tests. And I found out that a lot of best practices from software engineering can be adapted and applied to modern ops practices as well. DevOps in a nutshell really: Bridging the gap between Dev and Ops.

February 23, 2026 04:00 AM UTC

February 21, 2026

Brett Cannon

CLI subcommands with lazy imports

In case you didn&apost hear, PEP 810 got accepted which means Python 3.15 is going to support lazy imports! One of the selling points of lazy imports is with code that has a CLI so that you only import code as necessary, making the app a bit

February 21, 2026 10:37 PM UTC

Talk Python to Me

#537: Datastar: Modern web dev, simplified

You love building web apps with Python, and HTMX got you excited about the hypermedia approach -- let the server drive the HTML, skip the JavaScript build step, keep things simple. But then you hit that last 10%: You need Alpine.js for interactivity, your state gets out of sync, and suddenly you're juggling two unrelated libraries that weren't designed to work together. What if there was a single 11-kilobyte framework that gave you everything HTMX and Alpine do, and more, with real-time updates, multiplayer collaboration out of the box, and performance so fast you're actually bottlenecked by the monitor's refresh rate? That's Datastar. On this episode, I sit down with its creator Delaney Gillilan, core maintainer Ben Croker, and Datastar convert Chris May to explore how this backend-driven, server-sent-events-first framework is changing the way full-stack developers think about the modern web.

February 21, 2026 08:36 PM UTC

Django Weblog

DSF member of the month - Baptiste Mispelon

For February 2026, we welcome Baptiste Mispelon as our DSF member of the month! ⭐

Photo by Bartek Pawlik - bartpawlik.format.com

Photo by Bartek Pawlik - bartpawlik.format.com

Baptiste is a long-time Django and Python contributor who co-created the Django Under the Hood conference series and serves on the Ops team maintaining its infrastructure. He has been a DSF member since November 2014. You can learn more about Baptiste by visiting Baptiste's website and his GitHub Profile.

Let’s spend some time getting to know Baptiste better!

Can you tell us a little about yourself? (hobbies, education, etc)

I'm a French immigrant living in Norway. In the day time I work as software engineer at Torchbox building Django and Wagtail sites. Education-wise I'm a "self-taught" (whatever that means) developer and started working when I was very young. In terms of hobbies, I'm a big language nerd and I'm always up for a good etymology fact. I also enjoy the outdoor whether it's on a mountain bike or on foot (still not convinced by this skiing thing they do in Norway, but I'm trying).

How did you start using Django?

I was working in a startup where I had built an unmaintainable pile of custom framework-less PHP code. I'd heard of this cool Python framework and thought it would help me bring some structure to our codebase. So I started rewriting our services bit-by-bit and eventually switched everything to Django after about a year.

In 2012, I bought a ticket to DjangoCon Europe in Zurich and went there not knowing anyone. It was one of the best decisions of my life: the Django community welcomed me and has given me so much over the years.

What other framework do you know and if there is anything you would like to have in Django if you had magical powers?

I've been making website for more than two decades now, so I've used my fair share of various technologies and frameworks, but Django is still my "daily driver" and the one I like the best. I like writing plain CSS, and when I need some extra bit of JS I like to use Alpine JS and/or HTMX: I find they work really well together with Django.

If I had magical powers and could change anything, I would remove the word "patch" from existence (and especially from the Django documentation).

What projects are you working on now?

I don't have any big projects active at the moment, I'm mostly working on client projects at work.

Which Django libraries are your favorite (core or 3rd party)?

My favorite Django library of all time is possibly django-admin-dracula. It's the perfect combination of professional and whimsical for me.

Other than that I'm also a big fan of the Wagtail CMS. I've been learning more and more about it in the past year and I've really been liking it. The code feels very Django-y and the community around it is lovely as well.

What are the top three things in Django that you like?

1) First of course is the people. I know it's a cliche but the community is what makes Django so special.

2) In terms of the framework, what brought me to it in the first place was its opinionated structure and settings. When I started working with Django I didn't really know much about web development, but Django's standard project structure and excellent defaults meant that I could just use things out of the box knowing I was building something solid. And more than that, as my skills and knowledge grew I was able to swap out those defaults with some more custom things that worked better for me. There's room to grow and the transition has always felt very smooth for me.

3) And if I had to pick a single feature, then I'd go for one that I think is underrated: assertQuerySetEqual(). I think more people should be using it!

What is it like to be in the Ops team?

It's both very exciting and very boring 😅

Most of the tasks we do are very mundane: create DNS records, update a server, deploy a fix. But because we have access and control over a big part of the infrastructure that powers the Django community, it's also a big responsibility which we don't take lightly.

I know you were one of the first members of the Django Girls Foundation board of directors. That's amazing! How did that start for you?

By 2014 I'd become good friend with Ola & Ola and in July they asked me to be a coach at the very first Django Girls workshop at EuroPython in Berlin. The energy at that event was amazing an unlike any other event I'd been a part of, so I got hooked.

I went on to coach at many other workshops after that. When Ola & Ola had the idea to start an official entity for Django Girls, they needed a token white guy and I gladly accepted the role!

You co-created Django Under the Hood series which, from what I've heard, was very successful at the time. Can you tell us a little more about this conference and its beginnings?

I'm still really proud of having been on that team and of what we achieved with this conference. So many stories to tell!

I believe it all started at the Django Village conference where Marc Tamlin and I were looking for ideas for how to bring the Django core team together.

We thought that having a conference would be a good way to give an excuse (and raise funds) for people to travel all to the same place and work on Django. Somehow we decided that Amsterdam was the perfect place for that.

Then we were extremely lucky that a bunch of talented folks actually turned that idea into a reality: Sasha, Ola, Tomek, Ola, Remco, Kasia (and many others) 💖.

As a former conference organizer and volunteer, do you have any recommendations for those who want to contribute or organize a conference?

I think our industry (and even the world in general) is in a very different place today than a decade ago when I was actively organizing conferences. Honestly I'm not sure it would be as easy today to do the things we've done.

My recommendation is to do it if you can. I've forged some real friendships in my time as an organizer, and as exhausting and stressful as it can be, it's also immensely rewarding in its own way.

The hard lesson I'd also give is that you should pay attention to who gets to come to your events, and more importantly who doesn't. Organizing a conference is essentially making a million decisions, most of which are really boring. But every decision you make has an effect when it's combined with all the others. The food you serve or don't serve, the time of year your event takes place, its location. Whether you spend your budget on fun tshirts, or on travel grants.

All of it makes a difference somehow.

Do you remember your first contribution in Django?

I do! It was commit ac8eb82abb23f7ae50ab85100619f13257b03526: a one character typo fix in an error message 😂

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Open source is made of people, not code. You'll never go wrong by investing in your community. Claude will never love you back.

Thank you for doing the interview, Baptiste !

February 21, 2026 09:11 AM UTC

PyBites

3 Questions to go from thinking like a Scrappy to Senior Dev

How do you know if you’re actually growing as a dev? Last week I was chatting with a developer who’d hit a wall. (I talk to a lot of devs now that I think about it!) Like him, you might consider yourself a scrappy coder. You’re an all-rounder, can generally figure things out and write… Continue reading 3 Questions to go from thinking like a Scrappy to Senior Dev

February 21, 2026 09:00 AM UTC

February 20, 2026

Graham Dumpleton

Teaching an AI about Educates

The way we direct AI coding agents has changed significantly over the past couple of years. Early on, the interaction was purely conversational. You'd open a chat, explain what you wanted, provide whatever context seemed relevant, and hope the model could work with it. If it got something wrong or went down the wrong path, you'd correct it and try again. It worked, but it was ad hoc. Every session started from scratch. Every conversation required re-establishing context.

What's happened since then is a steady progression toward giving agents more structured, persistent knowledge to work with. Each step in that progression has made agents meaningfully more capable, to the point where they can now handle tasks that would have been unrealistic even a year ago. I've been putting these capabilities to work on a specific challenge: getting an AI to author interactive workshops for the Educates training platform. In my previous posts I talked about why workshop content is actually a good fit for AI generation. Here I want to explain how I've been making that work in practice.

How agent steering has evolved

The first real step beyond raw prompting was agent steering files. These are files you place in a project directory that give the agent standing instructions whenever it works in that context. Think of it as a persistent briefing document. You describe the project structure, the conventions to follow, the tools to use, and the agent picks that up automatically each time you interact with it. No need to re-explain the basics of your codebase every session. This was a genuine improvement, but the instructions are necessarily general-purpose. They tell the agent about the project, not about any particular domain of expertise.

The next step was giving agents access to external tools and data sources through protocols like the Model Context Protocol (MCP). Instead of the agent only being able to read and write files, it could now make API calls, query databases, fetch documentation, and interact with external services. The agent went from being a conversationalist that could edit code to something that could actually do things in the world. That opened up a lot of possibilities, but the agent still needed you to explain what to do and how to approach it.

Planning modes added another layer. Rather than the agent diving straight into implementation, it could first think through the approach, break a complex task into steps, and present a plan for review before acting. This was especially valuable for larger tasks where getting the overall approach right matters more than any individual step. The agent became more deliberate and less likely to charge off in the wrong direction.

Skills represent where things stand now, and they're the piece that ties the rest together. A skill is a self-contained package of domain knowledge, workflow guidance, and reference material that an agent can invoke when working on a specific type of task. Rather than the agent relying solely on what it learned during training, a skill gives it authoritative, up-to-date, structured knowledge about a particular domain. The agent knows when to use the skill, what workflow to follow, and which reference material to consult for specific questions.

With the advances in what LLMs are capable of combined with these structured ways of steering them, agents are genuinely reaching a point where their usefulness is growing in ways that matter for real work.

Why model knowledge isn't enough

Large language models know something about most topics. If you ask an AI about Educates, it will probably have some general awareness of the project. But general awareness is not the same as the detailed, precise knowledge you need to produce correct output for a specialised platform.

Educates workshops have specific YAML structures for their configuration files. The interactive instructions use a system of clickable actions with particular syntax for each action type. There are conventions around how learners interact with terminals and editors, how dashboard tabs are managed, how Kubernetes resources are configured, and how data variables are used for parameterisation. Getting any of these wrong doesn't just produce suboptimal content, it produces content that simply won't work when someone tries to use it.

I covered the clickable actions system in detail in my last post. There are eight categories of actions covering terminal execution, file viewing and editing, YAML-aware modifications, validation, and more. Each has its own syntax and conventions. An AI that generates workshop content needs to use all of these correctly, not approximately, not most of the time, but reliably.

This is where skills make the difference. Rather than hoping the model has absorbed enough Educates documentation during its training to get these details right, you give it the specific knowledge it needs. The skill becomes the agent's reference manual for the domain, structured in a way that supports the workflow rather than dumping everything into context at once.

The Educates workshop authoring skill

The obvious approach would be to take the full Educates documentation and load it into the agent's context. But AI agents work within a finite context window, and that window is shared between the knowledge you give the agent and the working space it needs for the actual task. Generating a workshop involves reasoning about structure, producing instruction pages, writing clickable action syntax, and keeping track of what's been created so far. If you consume most of the context with raw documentation, there's not enough room left for the agent to do its real work. You have to be strategic about what goes in.

The skill I built for Educates workshop authoring is a deliberate distillation. At its core is a main skill definition of around 25 kilobytes that captures the essential workflow an agent follows when creating a workshop. It covers gathering requirements from the user, creating the directory structure, generating the workshop configuration file, writing instruction pages with clickable actions, and running through verification checklists at the end. This isn't a copy of the documentation. It's the key knowledge extracted and organised to drive the workflow correctly.

Supporting that are 20+ reference files totalling around 300 kilobytes. These cover specific aspects of the platform in the detail needed to get things right: the complete clickable actions system across all eight action categories, Kubernetes access patterns and namespace isolation, data variables for parameterising workshop content, language-specific references for Python and Java workshops, dashboard configuration and tab management, workshop image selection, setup scripts, and more.

The skill is organised around the workflow rather than being a flat dump of information. The main definition tells the agent what to do at each step, and the reference files are there for it to consult when it needs detail on a particular topic. If it's generating a terminal action, it knows to check the terminal actions reference for the correct syntax. If it's setting up Kubernetes access, it consults the Kubernetes reference for namespace configuration patterns. The agent pulls in the knowledge it needs when it needs it, keeping the active context focused on the task at hand.

There's also a companion skill for course design that handles the higher-level task of planning multi-workshop courses, breaking topics into individual workshops, and creating detailed plans for each one. But the workshop authoring skill is where the actual content generation happens, and it's the one I want to demonstrate.

Putting it to the test with Air

To show what the skill can do, I decided to use it to generate a workshop for the Air web framework. Air is a Python web framework written by friends in the Python community. It's built on FastAPI, Starlette, and HTMX, with a focus on simplicity and minimal JavaScript. What caught my attention about it as a test case is the claim on their website: "The first web framework designed for AI to write. Every framework claims AI compatibility. Air was architected for it." That's a bold statement, and using Air as the subject for this exercise is partly a way to see how that claim holds up in practice, not just for writing applications with the framework but for creating training material about it.

There's another reason Air makes for a good test. I haven't used the framework myself. I know the people behind it, but I haven't built anything with it. That means I can't fall back on my own knowledge to fill in gaps. The AI needs to research the framework and understand it well enough to teach it to someone, while the skill provides all the Educates platform knowledge needed to structure that understanding into a proper interactive workshop. It's a genuine test of both the skill and the model working together.

The process starts simply enough. You tell the agent what you want: create me a workshop for the Educates training platform introducing the Air web framework for Python developers. The phrasing matters here. The agent needs enough context in the request to recognise that a relevant skill exists and should be applied. Mentioning Educates in the prompt is what triggers the connection to the workshop authoring skill. Some agents also support invoking a skill directly through a slash command, which removes the ambiguity entirely. Either way, once the skill is activated, its workflow kicks in. It asks clarifying questions about the workshop requirements. Does it need an editor? (Yes, learners will be writing code.) Kubernetes access? (No, this is a web framework workshop, not a Kubernetes one.) What's the target difficulty and duration?

I'd recommend using the agent's planning mode for this initial step if it supports one. Rather than having the agent jump straight into generating files, planning mode lets it first describe what it intends to put in the workshop: the topics it will cover, the page structure, and the learning progression. You can review that plan and steer it before any files are created. It's a much better starting point than generating everything and then discovering the agent went in a direction you didn't want.

From those answers and the approved plan, it builds up the workshop configuration and starts generating content.

lab-python-air-intro/

├── CLAUDE.md

├── README.md

├── exercises/

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── pyproject.toml

│ └── app.py

├── resources/

│ └── workshop.yaml

└── workshop/

├── setup.d/

│ └── 01-install-packages.sh

├── profile

└── content/

├── 00-workshop-overview.md

├── 01-first-air-app.md

├── 02-air-tags.md

├── 03-adding-routes.md

└── 99-workshop-summary.md

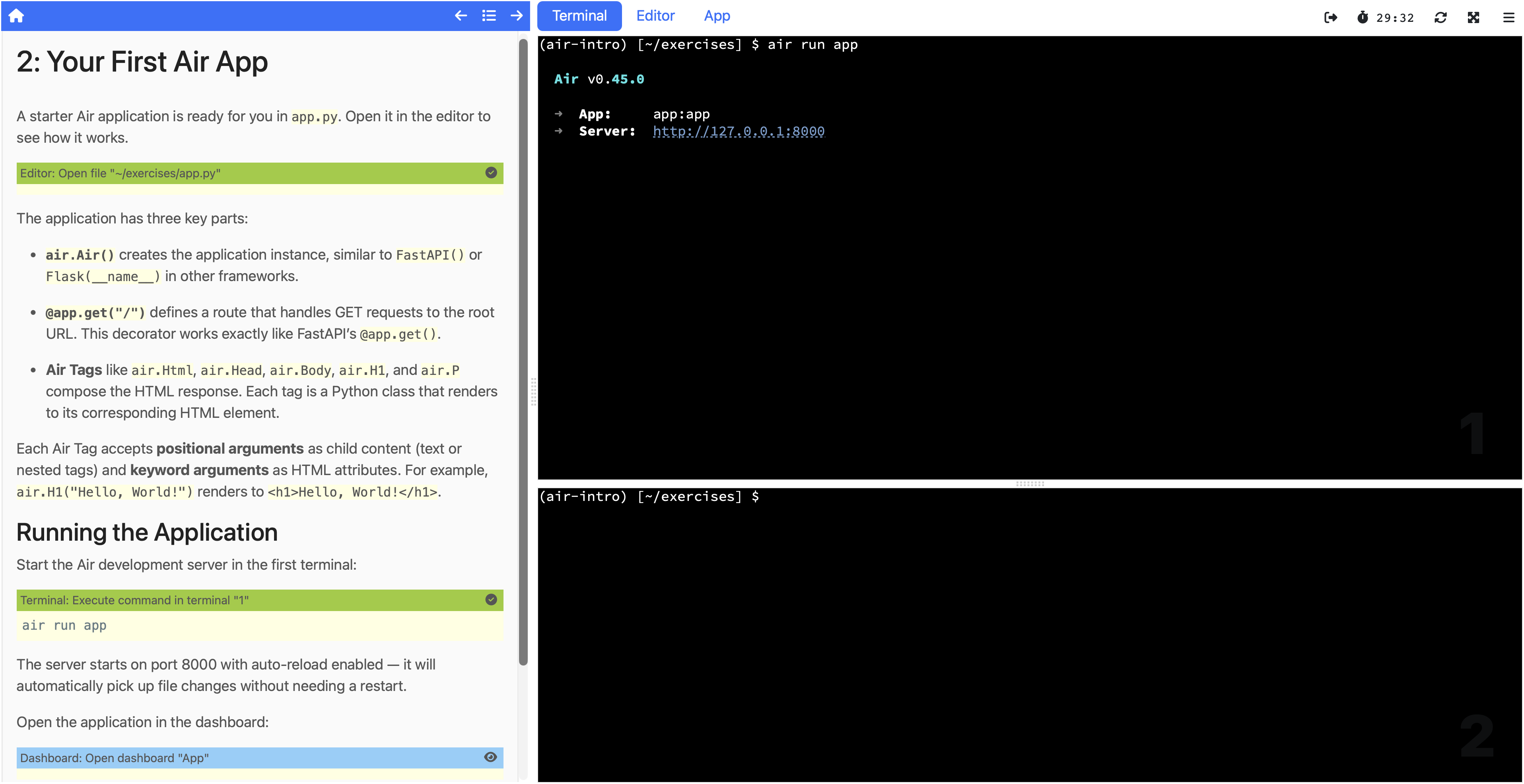

The generated workshop pages cover a natural learning progression:

- Overview, introducing Air and its key features

- Your First Air App, opening the starter

app.py, running it, and viewing it in the dashboard - Building with Air Tags, replacing the simple page with styled headings, lists, and a horizontal rule to demonstrate tag nesting, attributes, and composition

- Adding Routes, creating an about page with

@app.page, a dynamic greeting page with path parameters, and navigation links between pages - Summary, recapping concepts and pointing to further learning

What the skill produced is a complete workshop with properly structured instruction pages that follow the guided experience philosophy. Learners progress through the material entirely through clickable actions. Terminal commands are executed by clicking. Files are opened, created, and modified through editor actions. The workshop configuration includes the correct YAML structure, the right session applications are enabled, and data variables are used where content needs to be parameterised for each learner's environment.

The generated content covers the progression you'd want in an introductory workshop, starting from the basics and building up to more complete applications. At each step, the explanations provide context for what the learner is about to do before the clickable actions guide them through doing it. That rhythm of explain, show, do, observe, the pattern I described in my earlier posts, is maintained consistently throughout.

Is the generated workshop perfect and ready to publish as-is? Realistically, no. Although the AI can generate some pretty amazing content, it doesn't always get things exactly right. In this case three changes were needed before the workshop would run correctly.

The first was removing some unnecessary configuration from the pyproject.toml. The generated file included settings that attempted to turn the application into an installable package, which wasn't needed for a simple workshop exercise. This isn't a surprise. AI agents often struggle to generate correct configuration for uv because the tooling has changed over time and there's plenty of outdated documentation out there that leads models astray.

The second was that the AI generated the sample application as app.py rather than main.py, which meant the air run command in the workshop instructions had to be updated to specify the application name explicitly. A small thing, but the kind of inconsistency that would trip up a learner following the steps.

The third was an unnecessary clickable action. The generated instructions included an action for the learner to click to open the editor on the app.py file, but the editor would already have been displayed by a previous action. This one turned out to be a gap in the skill itself. When using clickable actions to manipulate files in the editor, the editor tab is always brought to the foreground as a side effect. The skill didn't make that clear enough, so the AI added a redundant step to explicitly show the editor tab.

That last issue is a good example of why even small details matter when creating a skill, and also why skills have an advantage over relying purely on model training. Because the skill can be updated at any time, fixing that kind of gap is straightforward. You edit the reference material, and every future workshop generation benefits immediately. You aren't dependent on waiting for some future LLM model release that happens to have seen more up-to-date documentation.

You can browse the generated files in the sample repository on GitHub. If you check the commit history you'll see how little had to be changed from what was originally generated.

Even with those fixes, the changes were minor. The overall structure was correct, the clickable actions worked, and the content provided a coherent learning path. What would have taken hours of manual authoring to produce (writing correct clickable action syntax, getting YAML configuration right, maintaining consistent pacing across instruction pages) the skill handles all of that. A domain expert would still want to review the content, verify the technical accuracy of the explanations, and adjust the pacing or emphasis based on what they think matters most for learners. But the job shifts from writing everything from scratch to reviewing and refining what was generated.

What this means

Skills are a way of packaging expertise so that it can be reused. The knowledge I've accumulated about how to author effective Educates workshops over years of building the platform is now encoded in a form that an AI agent can apply. Someone who has never created an Educates workshop before could use this skill and produce content that follows the platform's conventions correctly. They bring the subject matter knowledge (or the AI researches it), and the skill provides the platform expertise.

That's what makes this different from just asking an AI to "write a workshop." The skill encodes not just facts about the platform but the workflow, the design principles, and the detailed reference material that turn general knowledge into correct, structured output. It's the difference between an AI that knows roughly what a workshop is and one that knows exactly how to build one for this specific platform.

Both the workshop authoring skill and the course design skill are available now, and I'm continuing to refine them as I use them. If the idea of guided, interactive workshops appeals to you, the Educates documentation is the place to start. And if you're interested in exploring the use of AI to generate workshops for Educates, do reach out to me.

February 20, 2026 09:39 PM UTC

Clickable actions in workshops

The idea of guided instruction in tutorials isn't new. Most online tutorials these days provide a click-to-copy icon next to commands and code snippets. It's a useful convenience. You see the command you need to run, you click the icon, and it lands in your clipboard ready to paste. Better than selecting text by hand and hoping you got the right boundaries.

But this convenience only goes so far. The instructions still assume you have a suitable environment set up on your own machine. The commands might reference tools you haven't installed, paths that don't exist in your setup, or configuration that differs from what the tutorial expects. The copy button solves the mechanics of getting text into your clipboard, but the real friction is in the gap between the tutorial and your environment. You end up spending more time troubleshooting your local setup than actually learning the thing the tutorial was supposed to teach you.

Hosted environments and the copy/paste problem

Online training platforms like Instruqt and Strigo improved on this by providing VM-based environments that are pre-configured and ready to go. You don't need to install anything locally. The environment matches what the instructions expect, so commands and paths should work as written. That eliminates the entire class of problems around "works on the tutorial author's machine but not on mine."

The interaction model, though, is still copy and paste. You read instructions in one panel, find the command you need, copy it, switch to the terminal panel, paste it, and run it. For code changes, you copy a snippet from the instructions and paste it into a file in the editor. It works, but it's a manual process that requires constant context switching between panels. Every copy and paste is a small interruption, and over the course of a full workshop those interruptions add up. Learners end up spending mental energy on the mechanics of following instructions rather than on the material itself.

When commands became clickable

Katacoda, before it was shut down by O'Reilly in 2022, included an improvement to this model. Commands embedded in the workshop instructions were clickable. Click on a command and it would automatically execute in the terminal session provided alongside the instructions. No copying, no pasting, no switching between panels. The learner reads the explanation, clicks the command, and watches the result appear in the terminal. The flow from reading to doing became much more seamless.

This was a meaningful step forward for terminal interactions specifically. But it only covered one part of the workflow. For code changes, editing configuration files, or any interaction that involved working with files in an editor, you were still back to the copy and paste model. The guided experience had a gap. Commands were frictionless, but everything else still required manual effort.

Educates and the fully guided experience

Educates takes the idea of clickable actions and extends it across the entire workshop interaction. The workshop dashboard provides instructions alongside live terminals and an embedded VS Code editor. Throughout the instructions, learners encounter clickable actions that cover not just running commands, but the full range of things you'd normally do in a hands-on technical workshop.

Terminal actions work the way Katacoda relied on. Click on a command in the instructions and it runs in the terminal. But Educates goes further by providing a full set of editor actions as well. Clickable actions can open a file in the embedded editor, create a new file with specified content, select and highlight specific text within a file, and then replace that selected text with new content. You can append lines to a file, insert content at a specific location, or delete a range of lines. All of it driven by clicking on actions in the instructions rather than manually editing files.

Educates also includes YAML-aware editor actions, which is significant because YAML editing is notoriously error-prone when done by hand. A misplaced indent or a missing space after a colon can break an entire configuration file, and debugging YAML syntax issues is not what anyone signs up for in a workshop about Kubernetes or application deployment. The YAML actions let you reference property paths like spec.replicas or spec.template.spec.containers[name=nginx] and set values, add items to sequences, or replace entries, all while preserving existing comments and formatting in the file.

Beyond editing, Educates provides examiner actions that run validation scripts to check whether the learner has completed a step correctly. In effect, the workshop can grade the learner's work and provide immediate feedback. If they missed a step or made an error, they find out right away rather than discovering it three steps later when something else breaks. There are also collapsible section actions for hiding optional content or hints until the learner needs them, and file transfer actions for downloading files from the workshop environment to the learner's machine or uploading files into it.

The end result is that learners can progress through an entire workshop without ever manually typing a command, editing a file by hand, or wondering whether they've completed a step correctly. They focus on understanding the concepts being taught while the clickable actions handle the mechanics. That changes the experience fundamentally. Instead of the workshop being something you push through, it becomes something that carries you forward.

The dashboard in action

To get a sense for what this looks like in practice, here are a couple of screenshots from an Educates workshop.

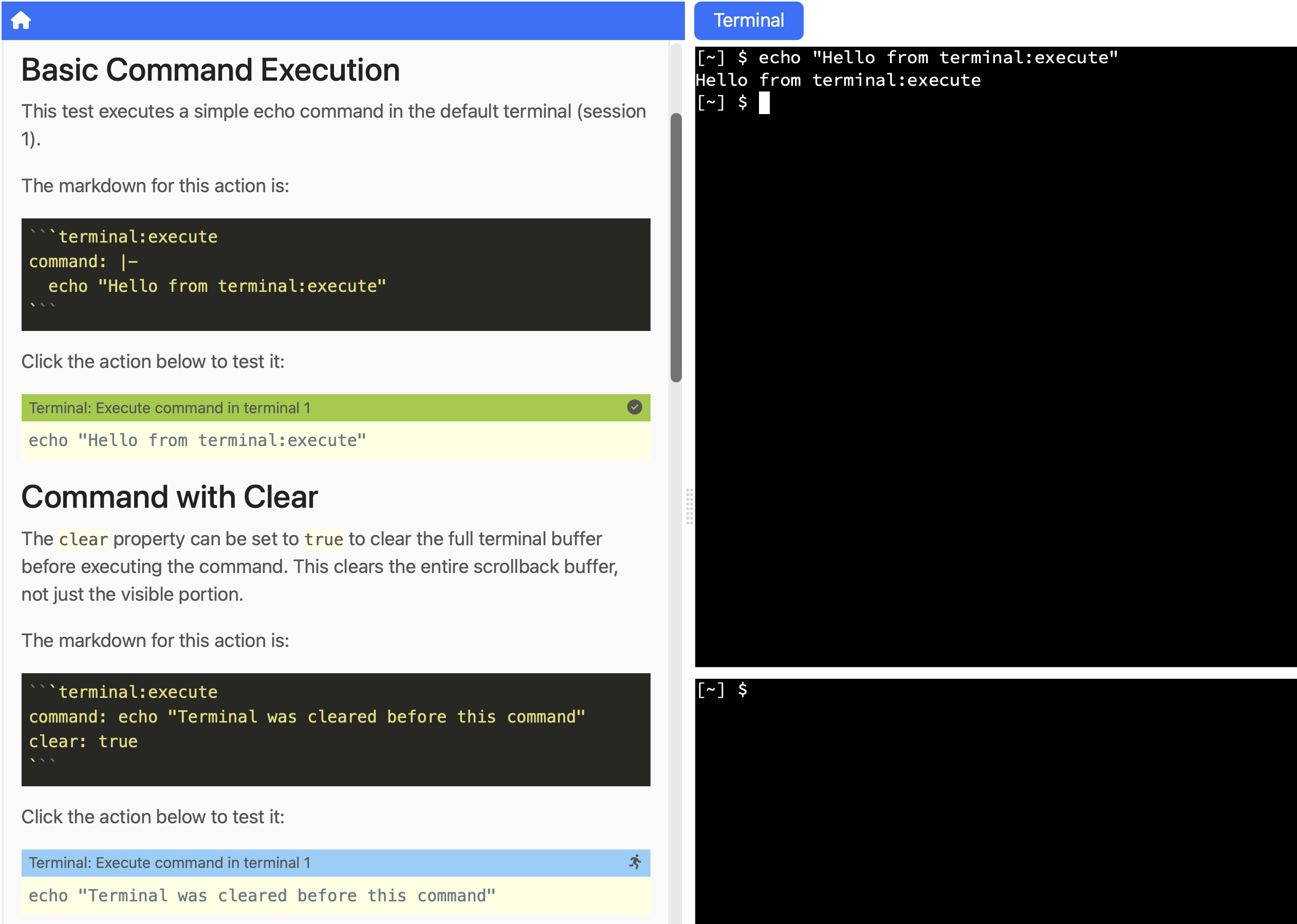

The instructions panel on the left contains a clickable action for running a command. When the learner clicks it, the command executes in the terminal panel and the output appears immediately. No copying, no pasting, no typing.

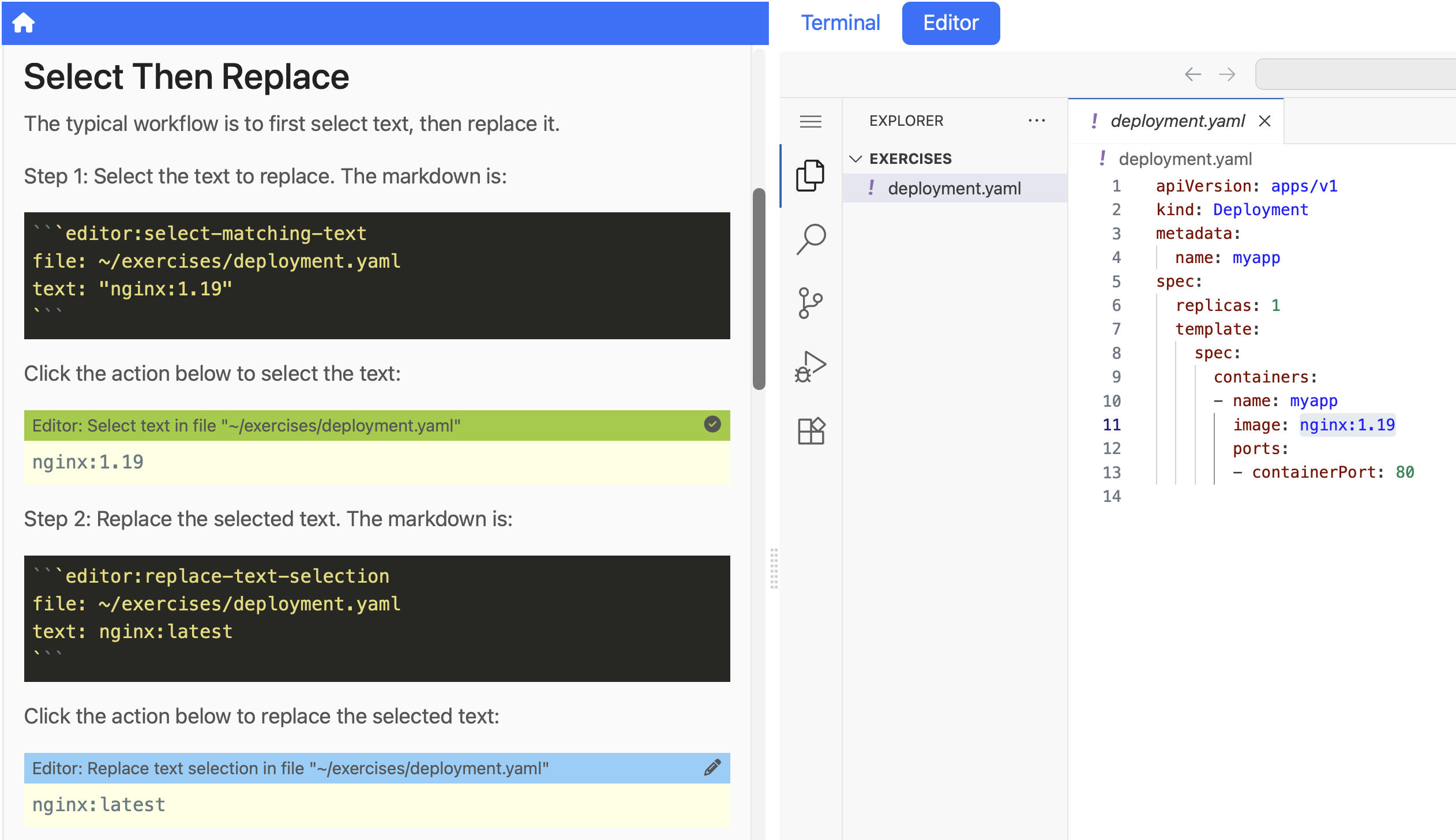

Here the embedded editor shows the result of a select-and-replace flow. The instructions guided the learner through highlighting specific text in a file and then replacing it with updated content, all through clickable actions. The learner sees exactly what changed and why, without needing to manually locate the right line and make the edit themselves.

How it works in the instructions

Workshop instructions in Educates are written in markdown. Clickable actions are embedded as specially annotated fenced code blocks where the language identifier specifies the action type and the body contains YAML configuration that controls what the action does.

For example, to guide a learner through updating an image reference in a Kubernetes deployment file, you might include two actions in sequence. The first selects the text that needs to change:

```editor:select-matching-text

file: ~/exercises/deployment.yaml

text: "image: nginx:1.19"

```

The second replaces the selected text with the new value:

```editor:replace-text-selection

file: ~/exercises/deployment.yaml

text: "image: nginx:latest"

```

When the learner clicks the first action, the matching text is highlighted in the editor so they can see exactly what will change. When they click the second, the replacement is applied. They understand the change being made because they see both the before and after states, but they don't need to manually find the right line, select the text, and type the replacement. The instructions guide them through it.

For terminal commands, the syntax is even simpler:

```terminal:execute

command: |-

echo "Hello from terminal:execute"

```

The YAML within each code block controls everything about the action: which file to operate on, what text to match or replace, which terminal session to use, and so on. The format is consistent across all action types. Once you understand the pattern of action type as the language identifier and YAML configuration as the body, authoring with actions is straightforward.

The value of removing friction

The progression from copy/paste tutorials to hosted environments to clickable commands to a fully guided experience like Educates is ultimately a progression toward removing every point where a learner might disengage. Each improvement eliminates another source of friction, another moment where someone might lose focus because they're fighting the tools instead of learning the material. When the mechanics of following instructions become invisible, learners stay engaged longer and absorb more of what the workshop is trying to teach.

In my previous post I discussed how this interactive format, combined with thoughtful use of AI for content generation, can produce workshop content that maintains consistent quality throughout. The clickable actions I've described here are what make that format possible. They're the mechanism that turns static instructions into a guided, interactive experience where the learner's attention stays on the concepts rather than the process.

In future posts I plan to write about how I'm using AI agent skills to automate the creation of Educates workshops, including the generation of all the clickable actions that drive the guided process along with the commentary and explanations the workshop instructions include. The goal is that the generated workshop runs out of the box, with the only remaining step being for the domain expert to validate the content and tweak where necessary. That has the potential to save a huge amount of time in creating workshops, making it practical to build high-quality guided learning experiences for topics that would otherwise never get the investment.

February 20, 2026 09:39 PM UTC

Real Python

The Real Python Podcast – Episode #285: Exploring MCP Apps & Adding Interactive UIs to Clients

How can you move your MCP tools beyond plain text? How do you add interactive UI components directly inside chat conversations? This week on the show, Den Delimarsky from Anthropic joins us to discuss MCP Apps and interactive UIs in MCP.

February 20, 2026 12:00 PM UTC

Graham Dumpleton

When AI content isn't slop

In my last post I talked about the forces reshaping developer advocacy. One theme that kept coming up was content saturation. AI has made it trivially easy to produce content, and the result is a flood of generic, shallow material that exists to fill space rather than help anyone. People have started calling this "AI slop," and the term captures something real. Recycled tutorials, SEO-bait blog posts, content that says nothing you couldn't get by asking a chatbot directly. There's a lot of it, and it's getting worse.

The backlash against AI slop is entirely justified. But I've been wondering whether it has started to go too far.

The backlash is justified

To be clear, the problem is real. You can see it every time you search for something technical. The same generic "getting started" guide, rewritten by dozens of different sites (or quite possibly the same AI), each adding nothing original. Shallow tutorials that walk through the basics without any insight from someone who has actually used the technology in practice. Content that was clearly produced to fill a content calendar rather than to answer a question anyone was actually asking.

Developers have become good at spotting this. Most can tell within a few seconds whether something was written by a person with genuine experience or generated to tick a box. That's a healthy instinct. The bar for content worth reading has gone up, and honestly, that's probably a good thing. There was plenty of low-effort content being produced by humans long before AI entered the picture.

But healthy skepticism can tip over into reflexive dismissal. "AI-generated" has become a label that gets applied broadly, and once it sticks, people stop evaluating the content on its merits. The assumption becomes that if AI was involved, the content can't be worth reading. That misses some important distinctions.

Not all AI content serves the same purpose

There are two very different ways to use AI for content. One is to mass-produce generic articles to flood search results or pad out a blog. The goal is volume, not value. Nobody designed the output with a particular audience in mind or thought carefully about what the content needed to achieve. That's slop, and the label fits.

The other is to use AI as a tool within a system you've designed, where the output has a specific structure, a specific audience, and a specific purpose. The human provides the intent and the domain knowledge. The AI helps execute within those constraints.

The problem with AI slop is not that AI generated it. The problem is that nobody designed it with care or purpose. There was no thought behind the structure, no domain expertise informing the content, no consideration for who would read it or what they'd take away from it. If you bring all of those things to the table, the output is a different thing entirely.

Workshop instructions aren't blog posts

I've been thinking about this because of my own project. Educates is an interactive training platform I've been working on for over five years (I mentioned it briefly in my earlier post when I started writing here again). It's designed for hands-on technical workshops where people learn by doing, not just by reading.

Anyone who has run a traditional workshop knows the problem. You give people a set of instructions, and half of them get stuck before they've finished the first exercise. Not because the concepts are hard, but because the mechanics are. They're copying long commands from a document, mistyping a path, missing a flag, getting an error that has nothing to do with what they're supposed to be learning. The experience becomes laborious. People switch off. They stop engaging with the material and start just trying to get through it.

Educates takes a different approach. Workshop instructions are displayed alongside live terminals and an embedded code editor. The instructions include things that learners can click on that perform actions for them. Click to run a command in the terminal. Click to open a file in the editor. Click to apply a code change. Click to run a test. The aim is to make the experience as frictionless as possible so that learners stay engaged throughout.

This creates a rhythm. You see code in context. You read an explanation of what it does and what needs to change. You click to apply the change. You click to run it and observe the result. At every step, learners are actively progressing through a guided flow rather than passively reading a wall of text. Their attention stays on the concepts being taught, not on the mechanics of following instructions. People learn more effectively because nothing about the process gives them a reason to disengage.

Where AI fits into this

Writing good workshop content by hand is hard. Not just because of the volume of writing, but because maintaining that engaging, well-paced flow across a full workshop takes sustained focus. It's one thing to write a good explanation for one section. It's another to keep that quality consistent across dozens of sections covering an entire topic. Humans get tired. Explanations become terse halfway through. Steps that should guide the learner smoothly start to feel rushed or incomplete. The very quality that makes workshops effective, keeping learners engaged from start to finish, is the hardest thing to sustain when you're writing it all by hand.

This is where AI, with the right guidance and steering, can actually do well. When you provide the content conventions for the platform, the structure of the workshop, and clear direction about the learning flow you want, AI can generate content that maintains consistent quality and pacing throughout. It doesn't get fatigued halfway through and start cutting corners on explanations. It follows the same pattern of explaining, showing, applying, and observing as carefully in section twenty as it did in section one.

That said, this only works because the content has a defined structure, a specific format, and a clear purpose. The human still provides the design and the domain expertise. The AI operates within those constraints. With review and iteration, the result can actually be superior to what most people would produce by hand for this kind of structured content. Not because AI is inherently better at explaining things, but because maintaining that engaging flow consistently across a full workshop is something humans genuinely struggle with.

Slop is a design problem, not a tool problem

The backlash against AI slop is well-founded. Content generated without intent, without structure, and without domain expertise behind it deserves to be dismissed. But the line should be drawn at intent and design, not at whether AI was involved in the process. Content that was designed with a clear purpose, structured for a specific use case, and reviewed by someone who understands the domain is not slop, regardless of how it was produced. Content that was generated to fill space with no particular audience in mind is slop, regardless of whether a human wrote it.

I plan to write more about Educates in future posts, including what makes the interactive workshop format effective and how it changes the way people learn. For now, the point is simpler. Before dismissing AI-generated content out of hand, it's worth asking what it was designed to do and whether it does that well.

And yes, this post was itself written with the help of AI, guided by the kind of intent, experience, and hands-on steering I've been talking about. The same approach I'm applying to generating workshop content. If the argument holds, it should hold here too.

February 20, 2026 12:00 AM UTC

February 19, 2026

Paolo Melchiorre

Django ORM Standalone⁽¹⁾: Querying an existing database

A practical step-by-step guide to using Django ORM in standalone mode to connect to and query an existing database using inspectdb.

February 19, 2026 11:00 PM UTC

PyBites

How Even Senior Developers Mess Up Their Git Workflow

There are few things in software engineering that induce panic quite like a massive git merge conflict. You pull down the latest code, open your editor, and suddenly your screen is bleeding with <<<<<<< HEAD markers. Your logic is tangled with someone else’s, the CSS is conflicting, and you realise you just wasted hours building… Continue reading How Even Senior Developers Mess Up Their Git Workflow

February 19, 2026 10:39 PM UTC

The Python Coding Stack

The Journey From LBYL to EAFP • [Club]

When it’s OK to just go for it and see what happens

February 19, 2026 10:26 PM UTC

Django Weblog

Plan to Adopt Contributor Covenant 3 as Django’s New Code of Conduct

Last month we announced our plan to adopt Contributor Covenant 3 as Django's new Code of Conduct through a multi-step process. Today we're excited to share that we've completed the first step of that journey!

What We've Done

We've merged new documentation that outlines how any member of the Django community can propose changes to our Code of Conduct and related policies. This creates a transparent, community-driven process for keeping our policies current and relevant.

The new process includes:

- Proposing Changes: Anyone can open an issue with a clear description of their proposed change and the rationale behind it.

- Community Review: The Code of Conduct Working Group will discuss proposals in our monthly meetings and may solicit broader community feedback through the forum, Discord, or DSF Slack.

- Approval and Announcement: Once consensus is reached, changes are merged and announced to the community. Changes to the Code of Conduct itself will be sent to the DSF Board for final approval.

How You Can Get Involved

We welcome and encourage participation from everyone in the Django community! Here's how you can engage with this process:

- Share Your Ideas: If you have suggestions for improving our Code of Conduct or related documentation, open an issue on our GitHub repo.

- Join the Discussion: Participate in community discussions about proposed changes on the forum, Discord, or DSF Slack. Keep it positive, constructive, and respectful.

- Stay Informed: Watch the Code of Conduct repository to follow along with proposed changes and discussions.

- Provide Feedback: Not comfortable with GitHub? You can also reach out via conduct@djangoproject.com, or look for anyone with the

Code of Conduct WGrole on Discord.

What's Next

We're moving forward with the remaining steps of our plan:

- Step 2 (target: March 15): Update our Enforcement Manual, Reporting Guidelines, and FAQs via pull request 91.

- Step 3 (target: April 15): Adopt the Contributor Covenant 3 with proposed changes from the working group.

Each step will have its own pull request where the community can review and provide feedback before we merge. We're committed to taking the time needed to incorporate your input thoughtfully.

Thank you for being part of this important work to make Django a more welcoming and inclusive community for everyone!

February 19, 2026 03:51 PM UTC

Real Python

Quiz: Python's tuple Data Type: A Deep Dive With Examples

Practice Python tuples: create, access, and unpack immutable sequences to write safer, clearer code. Reinforce basics and avoid common gotchas. Try the quiz.

February 19, 2026 12:00 PM UTC

PyCharm

LangChain Python Tutorial: 2026’s Complete Guide

If you’ve read the blog post How to Build Chatbots With LangChain, you may want to know more about LangChain. This blog post will dive deeper into what LangChain offers and guide you through a few more real-world use cases. And even if you haven’t read the first post, you might still find the info […]

February 19, 2026 10:40 AM UTC

February 18, 2026

Python Engineering at Microsoft

Python Environments Extension for VS Code

The February 2026 release This release includes the Python Environments extension... Keep on reading to learn more!

The post Python Environments Extension for VS Code appeared first on Microsoft for Python Developers Blog.

February 18, 2026 10:00 PM UTC

The Python Coding Stack

When "It Works" Is Not Good Enough • Live Workshops

You’ve been reading articles here on The Python Coding Stack.

February 18, 2026 05:13 PM UTC

Anarcat

net-tools to iproute cheat sheet

This is also known as: "ifconfig is not installed by default

anymore, how do I do this only with the ip command?"

I have been slowly training my brain to use the new commands but I

sometimes forget some. So, here's a couple of equivalence from the old

package to net-tools the new iproute2, about 10 years late:

net-tools |

iproute2 |

shorter form | what it does |

|---|---|---|---|

arp -an |

ip neighbor |

ip n |

|

ifconfig |

ip address |

ip a |

show current IP address |

ifconfig |

ip link |

ip l |

show link stats (up/down/packet counts) |

route |

ip route |

ip r |

show or modify the routing table |

route add default GATEWAY |

ip route add default via GATEWAY |

ip r a default via GATEWAY |

add default route to GATEWAY |

route del ROUTE |

ip route del ROUTE |

ip r d ROUTE |

remove ROUTE (e.g. default) |

netstat -anpe |

ss --all --numeric --processes --extended |

ss -anpe |

list listening processes, less pretty |

Another trick

Also note that I often alias ip to ip -br -c as it provides a

much prettier output.

Compare, before:

anarcat@angela:~> ip a

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host noprefixroute

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: wlan0: <NO-CARRIER,BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state DOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff permaddr xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx

altname wlp166s0

altname wlx8cf8c57333c7

4: virbr0: <NO-CARRIER,BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state DOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 192.168.122.1/24 brd 192.168.122.255 scope global virbr0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

20: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc fq_codel state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 192.168.0.108/24 brd 192.168.0.255 scope global dynamic noprefixroute eth0

valid_lft 40699sec preferred_lft 40699sec

After:

anarcat@angela:~> ip -br -c a

lo UNKNOWN 127.0.0.1/8 ::1/128

wlan0 DOWN

virbr0 DOWN 192.168.122.1/24

eth0 UP 192.168.0.108/24

I don't even need to redact MAC addresses! It also affects the display of the other commands, which look similarly neat.

Also imagine pretty colors above.

Finally, I don't have a cheat sheet for iw vs iwconfig (from

wireless-tools) yet. I just use NetworkManager now and rarely have

to mess with wireless interfaces directly.

Background and history

For context, there are traditionally two ways of configuring the network in Linux:

- the old way, with commands like

ifconfig,arp,routeandnetstat, those are part of the net-tools package - the new way, mostly (but not entirely!) wrapped in a single

ipcommand, that is the iproute2 package

It seems like the latter was made "important" in Debian in 2008,

which means every release since Debian 5 "lenny"  has featured the

has featured the

ip command.

The former net-tools package was demoted in December 2016 which

means every release since Debian 9 "stretch" ships without an

ifconfig command unless explicitly requested. Note that this was

mentioned in the release notes in a similar (but, IMHO, less

useful) table.

(Technically, the net-tools Debian package source still indicates it

is Priority: important but that's a bug I have just filed.)

Finally, and perhaps more importantly, the name iproute is hilarious

if you are a bilingual french speaker: it can be read as "I proute"

which can be interpreted as "I fart" as "prout!" is the sound a fart

makes. The fact that it's called iproute2 makes it only more

hilarious.

February 18, 2026 04:30 PM UTC

Real Python

How to Install Python on Your System: A Guide

Learn how to install the latest Python version on Windows, macOS, and Linux. Check your version and choose the best installation method for your system.

February 18, 2026 02:00 PM UTC

Hugo van Kemenade

A CLI to fight GitHub spam

gh triage spam #

We get a lot of spam in the CPython project.

A lot of it isn’t even slop, but mostly worthless “nothing” issues and PRs that barely fill in the issue template, or add a line of nonsense to some arbitrary file.

They’re often from new accounts with usernames like:

- za9066559-wq

- quanghuynh10111-png

- riffocristobal579-cmd

- sajjad5giot

- satyamchoudhary1430-boop

- SilaMey

- standaell1234-maker

- eedamhmd2005-ui

- ksdmyanmar-lighter

- experments-studios

- madurangarathanayaka5-art

A new issue from a username following the pattern nameNNNN-short_suffix is a dead

giveaway. I think they’re trying to farm “realistic” accounts: open a PR, open an issue,

comment on something, make a fake review.

It’s easy but tedious to:

- close the PR/issue as not planned

- retitle to “spam”

- apply the “invalid” label

- remove other labels

I use the GitHub CLI gh a lot (for example, gh co NNN to check out a PR locally),

and it’s straightforward to write your own Python-based extensions, so I wrote

gh triage.

Install:

$ gh extension install hugovk/gh-triage

Cloning into '/Users/hugo/.local/share/gh/extensions/gh-triage'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 15, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (15/15), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (13/13), done.

remote: Total 15 (delta 5), reused 12 (delta 2), pack-reused 0 (from 0)

Receiving objects: 100% (15/15), 5.09 KiB | 5.09 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (5/5), done.

✓ Installed extension hugovk/gh-triage

Then run like gh triage spam <issue-or-pr-number-or-url>:

$ gh triage spam https://github.com/python/cpython/issues/144900

✅ Removed labels: type-bug

✅ Added labels: invalid

✅ Changed title: spam

✅ Closed

This can be used for any repo that you have permissions for: it applies the “invalid” or “spam” labels, but only if they exist in the repo.

Next step: perhaps it could print out the URL to make it easy to report the account to GitHub (usually for “Spam or inauthentic Activity”).

gh triage unassign #

Not spam, but another triage helper.

A less common occurrence is a rebase or merge from main or change of PR base branch

that ends up bringing in lots of code changes. This often assigns the PR to dozens of

people via

CODEOWNERS,

for example:

python/cpython#142564.

Everyone’s already been pinged and subscribed to the PR, so it’s too late to help that, but we can automate unassigning them all so at least the PR is not in their “assigned to” list.

Run gh triage unassign <issue-or-pr-number-or-url> to:

- remove all assignees (issues and PRs)

- remove all requested reviewers (PRs only)

For example:

gh triage unassign 142564

See also #

gh triagehomepage- Adam Johnson’s

top

ghcommands

Header photo: Otto of the Silver Hand written and illustrated by William Pyle, originally published 1888, from the University of California Libraries.

February 18, 2026 01:35 PM UTC

Real Python

Quiz: How to Install Python on Your System: A Guide

In this quiz, you'll test your understanding of how to install or update Python on your computer. With this knowledge, you'll be able to set up Python on various operating systems, including Windows, macOS, and Linux.

February 18, 2026 12:00 PM UTC

PyPodcats

Trailer: Episode 11 With Sheena O'Connell

A preview of our chat with Sheena O'Connell. Watch the full episode on February 26, 2026

February 18, 2026 05:00 AM UTC

February 17, 2026

PyCoder’s Weekly

Issue #722: Itertools, Circular Imports, Mock, and More (Feb. 17, 2026)

February 17, 2026 07:30 PM UTC

Real Python

Write Python Docstrings Effectively

Learn to write clear, effective Python docstrings using best practices, common styles, and built-in conventions for your code.

February 17, 2026 02:00 PM UTC

Python Software Foundation

Join the Python Security Response Team!